A. schaalii

Actinotignum schaalii (previously known as Actinobaculum schaalii)

Clinical Summary

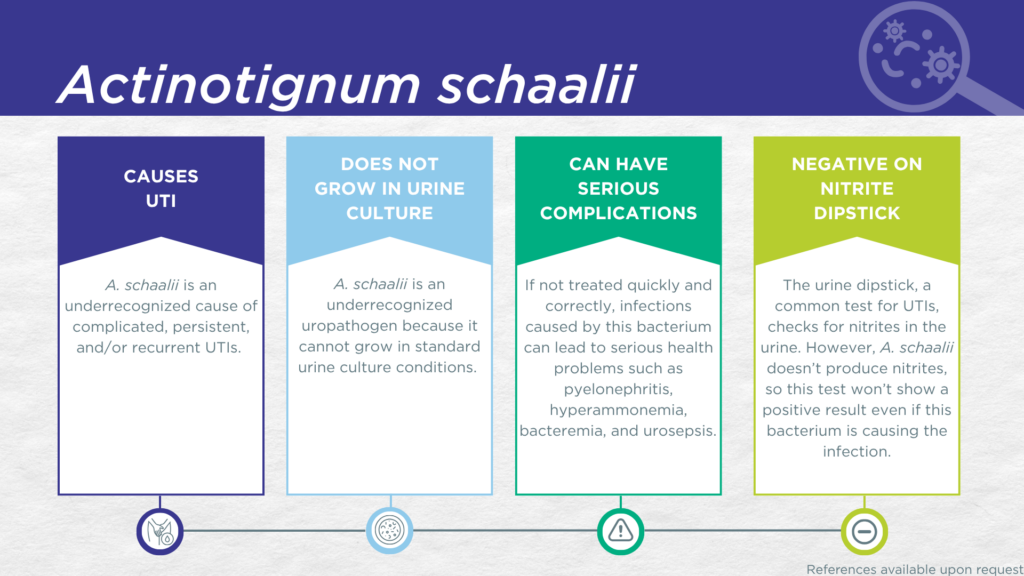

- A. schaalii is a nitrite-negative, biofilm-forming, gram-positive microorganism.

- A. schaalii is fastidious and cannot grow in standard urine culture conditions.

- A. schaalii is associated with complicated UTIs in young children, older adults, and individuals with urinary tract abnormalities.

- In symptomatic UTI patients, A. schaalii:

- Is not a contaminant (is found in catheter-collected urine specimens).

- Is viable (can grow out in expanded culture conditions).

- Is pathogenic (associated with elevated urine biomarkers of infection).

- Reported severe complications of A. schaalii UTI include pyelonephritis, hyperammonemia, bacteremia, and urosepsis.

Bacterial Characteristics

Gram-stain

Gram-positive

Morphology

Coccobacillus (intermediate between round and rod-shaped)

Growth Requirements

Fastidious (slow growing, prefers blood-agar)

Anaerobe/microaerophile

Nitrate Reduction

No

Urease

Negative

Biofilm Formation

Yes

Pathogenicity

Colonizer or Pathobiont

Clinical Relevance in UTI

A. schaalii was first identified as a human pathogen and classified as Actinobaculum schaalii in 1997 when the novel Actinobaculum genus was described.[1] In 2015 the Actinobaculum genus was split into Actinobaculum and Actinotignum, with A. schaalii being reclassified as Actinotignum schaalii.[2]

A. schaalii has been recognized for over a decade as a resident of the human urogenital microbiome.[3] By 2016 it had also been reported as the cause of at least 121 urinary tract infections,[4] predominantly in older adults,[5,6] young children, [7,8] and individuals with urinary tract abnormalities [9–12]. A. schaalii has also been reported to participate in the formation of polymicrobial biofilms on indwelling catheters.[13]

A. schaalii UTIs are likely significantly underdiagnosed due to the numerous challenges in the identification of A. schaalii.[4,14] Firstly, A. schaalii lacks nitrate reductase activity, so screening strategies involving urinalysis for nitrite positivity will be false-negative.[15,16] Secondly, growing A. schaalii in culture requires an anaerobic atmosphere with at least 5% CO2, particular nutritional requirements (blood agar medium), and extended incubation times of 48-72 hours.[14] These conditions are not typically used in clinical laboratories performing standard culture techniques for UTI diagnosis. Thirdly, even when this organism does grow in culture, it is often overgrown by other faster-growing species or dismissed as an irrelevant gram-positive commensal organism of the urogenital microbiome and labeled as a “contaminant”.[14] Instead, A. schaalii UTI is most often diagnosed by advanced proteomic techniques, such as Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS), or advanced molecular techniques, including polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and sequencing.[4,11,14,17]

A study using expanded quantitative urine culture (EQUC), a technique growing a larger urine volume with additional nutritional media, different atmospheric conditions, and longer incubations, found that the organism was viable.[18] In a study of older adult males and females with clinically suspected complicated UTI, A. schaalii was detected in both midstream voided and in-and-out-catheter collected specimens indicating that it was truly present in the bladder, not simply a contaminant picked up during voiding.[19] Furthermore, elevated markers of immune system activation in the urinary tract have been measured from the same clinical urine specimens in which A. schaalii was detected, indicating that the presence of A. schaalii was associated with an immune response to urinary tract infection.[20–22]

Critically, A. schaalii UTIs have also been reported to be resistant to several antibiotics [12] and to result in severe complications, including hyperammonemia [23] and progression to pyelonephritis,[10,24] bacteremia, [24,25] and even urosepsis [26]. Therefore, rapid and accurate diagnosis of A. schaalii as a causative pathogen in cases of cystitis is crucial for the prevention of urosepsis in at-risk individuals, including young children, older adults, individuals with urinary tract abnormalities, and individuals with significant comorbidities.[4]

Together, these findings demonstrate the value of detecting this organism and indicate that A. schaalii should be seriously considered as a uropathogen when detected in any individual with UTI symptoms.

Treatment

Evidence of Efficacy (Checkmarks) [4,27–29]: Amoxicillin/Clavulanate, Ampicillin/Sulbactam, Ampicillin, Ceftriaxone, Gentamicin, Levofloxacin, Linezolid, Nitrofurantoin, and Vancomycin.

1. Lawson, P.A.; Falsen, E.; Åkervall, E.; Vandamme, P.; Collins, M.D. Characterization of Some Actinomyces-Like Isolates from Human Clinical Specimens: Reclassification of Actinomyces Suis (Soltys and Spratling) as Actinobaculum Suis Comb. Nov. and Description of Actinobaculum Schaalii Sp. Nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 1997, 47, 899–903, doi:10.1099/00207713-47-3-899.

2. Yassin, A.F.; Spröer, C.; Pukall, R.; Sylvester, M.; Siering, C.; Schumann, P. Dissection of the Genus Actinobaculum: Reclassification of Actinobaculum Schaalii Lawson et al. 1997 and Actinobaculum Urinale Hall et al. 2003 as Actinotignum Schaalii Gen. Nov., Comb. Nov. and Actinotignum Urinale Comb. Nov., Description of Actinotignum Sanguinis Sp. Nov. and Emended Descriptions of the Genus Actinobaculum and Actinobaculum Suis; and Re-Examination of the Culture Deposited as Actinobaculum Massiliense CCUG 47753T ( = DSM 19118T), Revealing That It Does Not Represent a Strain of This Species. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 615–624, doi:10.1099/ijs.0.069294-0.

3. Olsen, A.B.; Andersen, P.K.; Bank, S.; Søby, K.M.; Lund, L.; Prag, J. Actinobaculum Schaalii, a Commensal of the Urogenital Area. BJU Int. 2013, 112, 394–397, doi:10.1111/j.1464-410x.2012.11739.x.

4. Lotte, R.; Lotte, L.; Ruimy, R. Actinotignum Schaalii (Formerly Actinobaculum Schaalii): A Newly Recognized Pathogen—Review of the Literature. Clin Microbiol Infec 2016, 22, 28–36, doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2015.10.038.

5. Nielsen, H.; Søby, K.; Christensen, J.; Prag, J. Actinobaculum Schaalii: A Common Cause of Urinary Tract Infection in the Elderly Population. Bacteriological and Clinical Characteristics. Scand J Infect Dis 2009, 42, 43–47, doi:10.3109/00365540903289662.

6. Bank, S.; Jensen, A.; Hansen, T.M.; Søby, K.M.; Prag, J. Actinobaculum Schaalii, a Common Uropathogen in Elderly Patients, Denmark. Emerg Infect Dis 2010, 16, 76–80, doi:10.3201/eid1601.090761.

7. Andersen, L.B.; Bank, S.; Hertz, B.; Søby, K.M.; Prag, J. Actinobaculum Schaalii, a Cause of Urinary Tract Infections in Children? Acta Paediatr 2012, 101, e232–e234, doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02586.x.

8. Zimmermann, P.; Berlinger, L.; Liniger, B.; Grunt, S.; Agyeman, P.; Ritz, N. Actinobaculum Schaalii an Emerging Pediatric Pathogen? BMC Infect. Dis. 2012, 12, 201, doi:10.1186/1471-2334-12-201.

9. Washio, M.; Harada, N.; Nishima, D.; Takemoto, M. Actinotignum Schaalii Can Be an Uropathogen of “Culture-Negative” Febrile Urinary Tract Infections in Children with Urinary Tract Abnormalities. Case Reports Nephrol Dialysis 2022, 12, 150–156, doi:10.1159/000526398.

10. Jayaweera, J.A.A.S.; Ranasinghe, G. Actinotignum Schaalii Pyelonephritis in a Young Adult with Ureteric Calculus: Case Report. Germs 2024, 14, 101–104, doi:10.18683/germs.2024.1422.

11. Bank, S.; Hansen, T.M.; Søby, K.M.; Lund, L.; Prag, J. Actinobaculum Schaalii in Urological Patients, Screened with Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2011, 45, 406–410, doi:10.3109/00365599.2011.599333.

12. Beguelin, C.; Genne, D.; Varca, A.; Tritten, M. ‐L.; Siegrist, H.H.; Jaton, K.; Lienhard, R. Actinobaculum Schaalii: Clinical Observation of 20 Cases. Clin Microbiol Infec 2011, 17, 1027–1031, doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03370.x.

13. Kotásková, I.; Syrovátka, V.; Obručová, H.; Vídeňská, P.; Zwinsová, B.; Holá, V.; Blaštíková, E.; Růžička, F.; Freiberger, T. Actinotignum Schaalii: Relation to Concomitants and Connection to Patients’ Conditions in Polymicrobial Biofilms of Urinary Tract Catheters and Urines. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 669, doi:10.3390/microorganisms9030669.

14. Sahuquillo-Arce, J.M.; Suárez-Urquiza, P.; Hernández-Cabezas, A.; Tofan, L.; Chouman-Arcas, R.; García-Hita, M.; Sabalza-Baztán, O.; Sellés-Sánchez, A.; Lozano-Rodríguez, N.; Martí-Cuñat, J.; et al. Actinotignum Schaalii Infection: Challenges in Diagnosis and Treatment. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28589, doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e28589.

15. BacDive | The Bacterial Diversity Metadatabase Available online: https://bacdive.dsmz.de/ (accessed on 11 February 2025).

16. BioCyc Pathway/Genome Database Collection Available online: https://biocyc.org/ (accessed on 11 February 2025).

17. Stevens, R.P.; Taylor, P.C. Actinotignum (Formerly Actinobaculum) Schaalii: A Review of MALDI-TOF for Identification of Clinical Isolates, and a Proposed Method for Presumptive Phenotypic Identification. Pathology 2016, 48, 367–371, doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2016.03.006.

18. Festa, R.A.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Parnell, L.; Wang, D.; Zhao, X.; Magallon, J.; Remedios-Chan, M.; Nguyen, J.; Cho, T.; et al. A Test Combining Multiplex-PCR with Pooled Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing Has High Correlation with Expanded Urine Culture for Detection of Live Bacteria in Urine Samples of Suspected UTI Patients. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2023, 107, 116015, doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2023.116015.

19. Wang, D.; Haley, E.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.; Zhao, X.; Anderson, L.A.; Allison, J.L.; Stebbins, K.L.; Diaz, M.J.; et al. Emerging and Fastidious Uropathogens Were Detected by M-PCR with Similar Prevalence and Cell Density in Catheter and Midstream Voided Urine Indicating the Importance of These Microbes in Causing UTIs. Infect. Drug Resist. 2023, Volume 16, 7775–7795, doi:10.2147/idr.s429990.

20. Haley, E.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.A.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Anderson, L.A.; Baunoch, D. The Prevalence and Association of Different Uropathogens Detected by M-PCR with Infection-Associated Urine Biomarkers in Urinary Tract Infections. Res. Rep. Urol. 2024, 16, 19–29, doi:10.2147/rru.s443361.

21. Akhlaghpour, M.; Haley, E.; Parnell, L.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.A.; Percaccio, M.; Magallon, J.; Remedios-Chan, M.; Rosas, A.; et al. Urine Biomarkers Individually and as a Consensus Model Show High Sensitivity and Specificity for Detecting UTIs. BMC Infect Dis 2024, 24, 153, doi:10.1186/s12879-024-09044-2.

22. Parnell, L.K.D.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.A.; Haley, E.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Anderson, L.; Baunoch, D. Elevated UTI Biomarkers in Symptomatic Patients with Urine Microbial Densities of 10,000 CFU/ML Indicate a Lower Threshold for Diagnosing UTIs. MDPI 2023, 13, 1–15, doi:10.3390/diagnostics13162688.

23. Nakamura, A.; Odo, M. Hyperammonemia and Impaired Consciousness Caused by Non-Urease-Producing Actinotignum Schaalii in Obstructive Urinary Tract Infection. Cureus 2024, 16, e76167, doi:10.7759/cureus.76167.

24. Lotte, L.; Durand, C.; Chevalier, A.; Gaudart, A.; Cheddadi, Y.; Ruimy, R.; Lotte, R. Acute Pyelonephritis with Bacteremia in an 89-Year-Old Woman Caused by Two Slow-Growing Bacteria: Aerococcus Urinae and Actinotignum Schaalii. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2908, doi:10.3390/microorganisms11122908.

25. Ueno, W.; Murata, Y.; Shirane, S.; Saito, Y.; Osawa, Y. Actinotignum Schaalii Can Cause Bacteremia in Children Without Urogenital Abnormalities: A Case Report. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2024, 43, e332–e333, doi:10.1097/inf.0000000000004381.

26. Brun, C.L.; Robert, S.; Tanchoux, C.; Bruyere, F.; Lanotte, P. Urinary Tract Infection Caused by Actinobaculum Schaalii: A Urosepsis Pathogen That Should Not Be Underestimated. Jmm Case Reports 2015, 2, doi:10.1099/jmmcr.0.000030.

27. Beguelin, C.; Genne, D.; Varca, A.; Tritten, M. ‐L.; Siegrist, H.H.; Jaton, K.; Lienhard, R. Actinobaculum Schaalii: Clinical Observation of 20 Cases. Clin Microbiol Infec 2011, 17, 1027–1031, doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03370.x.

28. Cattoir, V.; Varca, A.; Greub, G.; Prod’hom, G.; Legrand, P.; Lienhard, R. In Vitro Susceptibility of Actinobaculum Schaalii to 12 Antimicrobial Agents and Molecular Analysis of Fluoroquinolone Resistance. J Antimicrob Chemoth 2010, 65, 2514–2517, doi:10.1093/jac/dkq383.

29. Sahuquillo-Arce, J.M.; Suárez-Urquiza, P.; Hernández-Cabezas, A.; Tofan, L.; Chouman-Arcas, R.; García-Hita, M.; Sabalza-Baztán, O.; Sellés-Sánchez, A.; Lozano-Rodríguez, N.; Martí-Cuñat, J.; et al. Actinotignum Schaalii Infection: Challenges in Diagnosis and Treatment. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28589, doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e28589.