P. mirabilis

Emery Haley, PhD, Scientific Writing Specialist

Proteus mirabilis

Clinical Summary

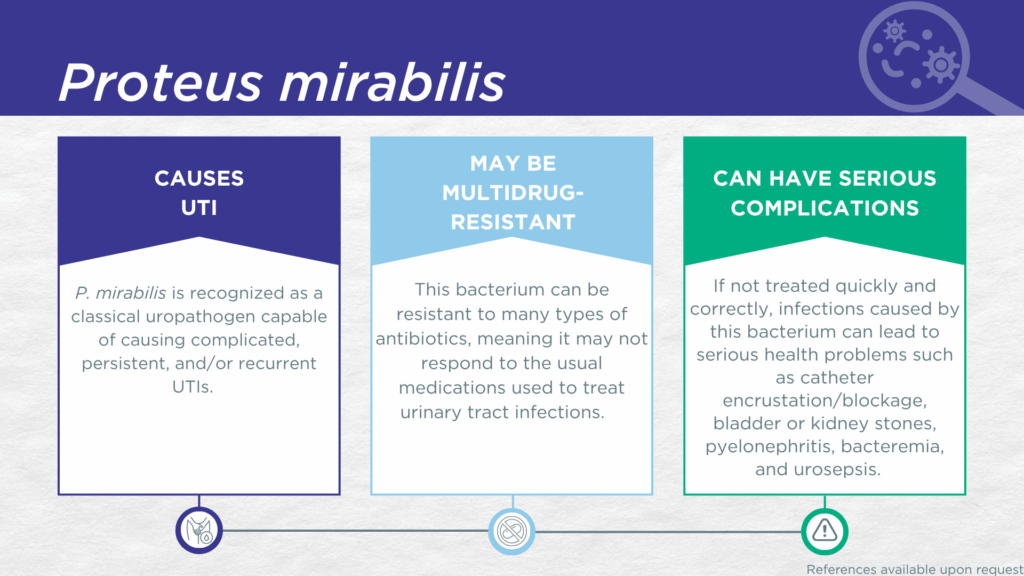

- P. mirabilis is recognized as a classical, urease-positive, gram-negative, biofilm-forming, motile uropathogen.

- P. mirabilis is primarily associated with complicated and persistent catheter-associated UTIs.

- In symptomatic UTI patients, P. mirabilis:

- Is not a contaminant (is found in catheter-collected urine specimens).

- Is viable (can grow out on culture).

- Is pathogenic (associated with elevated urine biomarkers of infection).

- Reported severe complications of P. mirabilis UTI include catheter encrustation/blockage, bladder or kidney stones, pyelonephritis, bacteremia, urosepsis, and death.

- Multidrug-resistant P. mirabilis is a significant global health threat.

Bacterial Characteristics

Gram-stain

Gram-negative

Morphology

Bacillus

Growth Requirements

Non-fastidious (grows well in standard urine culture conditions)

Facultative anaerobe

Nitrate Reduction

Yes

Urease

Positive

Biofilm Formation

Yes

Pathogenicity

Colonizer or Pathobiont

Clinical Relevance in UTI

P. mirabilis is a urease-positive,[1]gram-negative, biofilm-forming, motile bacillus classically recognized as a uropathogen. P. mirabilis is particularly well-known both for its swarming motility behavior, which is visible on culture plates and for forming crystalline biofilms on indwelling catheters.[2]

P. mirabilis is infamous for forming multidrug-resistant, polymicrobial, biofilms on indwelling urinary catheters, resulting in catheter-associated UTIs (CAUTIs).[3–5] In preclinical studies, P. mirabilis demonstrated synergism with both Enterococcus species and P. stuartii, including increased urease activity, urolithiasis, cell/tissue damage, and bacteremia.[5,6] In contrast, P. mirabilis exhibits antagonism with E. coli and M. morganii.[5]

This organism’s tendency to form biofilms on urinary catheters and to travel up the urinary tract toward the kidney, as well as its intrinsic and acquired resistance to several classes of antibiotics makes this uropathogen particularly challenging to treat.[2,4,7] In a study of older adult males and females with clinically suspected complicated UTI, P. mirabilis was detected in both midstream voided and in-and-out-catheter collected specimens indicating that it was truly present in the bladder, not simply a contaminant picked up during voiding.[8] Furthermore, elevated markers of immune system activation in the urinary tract have been measured from the same clinical urine specimens in which P. mirabilis was detected, indicating that the presence of P. mirabilis was associated with an immune response to urinary tract infection.[9–11]

Although not considered one of the six highest priority “ESKAPE” pathogens, The World Health Organization (WHO) has included this organism in the 2024 Bacterial Priority Pathogens List (BPPL).[12] Reported severe complications of P. mirabilis UTI include catheter encrustation/blockage, bladder or kidney stones, pyelonephritis, bacteremia, urosepsis, and death.[4,13,14]

Together, these findings indicate that P. mirabilis should be seriously considered as a uropathogen and demonstrate the value of detecting this organism, particularly in individuals with indwelling catheters or other risk factors for complicated UTI.

Treatment

Evidence of Efficacy (Checkmarks): Amoxicillin/Clavulanate, Ampicillin, Ampicillin/Sulbactam, Cefaclor, Cefazolin, Cefepime, Ceftazidime, Ceftriaxone, Ciprofloxacin, Gentamicin, Levofloxacin, Meropenem, Piperacillin/Tazobactam, Sulfamethoxazole/Trimethoprim, and Trimethoprim.

1. BacDive | The Bacterial Diversity Metadatabase Available online: https://bacdive.dsmz.de/ (accessed on 11 February 2025).

2. Fox-Moon, S.M.; Shirtliff, M.E. Molecular Medical Microbiology. 2024, 1299–1312, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-818619-0.00116-7.

3. Hunt, B.C.; Brix, V.; Vath, J.; Guterman, L.B.; Taddei, S.M.; Deka, N.; Learman, B.S.; Brauer, A.L.; Shen, S.; Qu, J.; et al. Metabolic Interplay between Proteus Mirabilis and Enterococcus Faecalis Facilitates Polymicrobial Biofilm Formation and Invasive Disease. mBio 2024, 15, e02164-24, doi:10.1128/mbio.02164-24.

4. Yuan, F.; Huang, Z.; Yang, T.; Wang, G.; Li, P.; Yang, B.; Li, J. Pathogenesis of Proteus Mirabilis in Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections. Urol. Int. 2021, 105, 354–361, doi:10.1159/000514097.

5. Gaston, J.R.; Johnson, A.O.; Bair, K.L.; White, A.N.; Armbruster, C.E. Polymicrobial Interactions in the Urinary Tract: Is the Enemy of My Enemy My Friend? Infect Immun 2021, 89, doi:10.1128/iai.00652-20.

6. Armbruster, C.E.; Smith, S.N.; Yep, A.; Mobley, H.L. Increased Incidence of Urolithiasis and Bacteremia During Proteus Mirabilis and Providencia Stuartii Coinfection Due to Synergistic Induction of Urease Activity. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2014, 209, 1524–1532, doi:10.1093/infdis/jit663.

7. Mirzaei, A.; Esfahani, B.N.; Raz, A.; Ghanadian, M.; Moghim, S. From the Urinary Catheter to the Prevalence of Three Classes of Integrons, Β‐Lactamase Genes, and Differences in Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Proteus Mirabilis and Clonal Relatedness with Rep‐PCR. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 9952769, doi:10.1155/2021/9952769.

8. Wang, D.; Haley, E.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.; Zhao, X.; Anderson, L.A.; Allison, J.L.; Stebbins, K.L.; Diaz, M.J.; et al. Emerging and Fastidious Uropathogens Were Detected by M-PCR with Similar Prevalence and Cell Density in Catheter and Midstream Voided Urine Indicating the Importance of These Microbes in Causing UTIs. Infect. Drug Resist. 2023, Volume 16, 7775–7795, doi:10.2147/idr.s429990.

9. Haley, E.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.A.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Anderson, L.A.; Baunoch, D. The Prevalence and Association of Different Uropathogens Detected by M-PCR with Infection-Associated Urine Biomarkers in Urinary Tract Infections. Res. Rep. Urol. 2024, 16, 19–29, doi:10.2147/rru.s443361.

10. Akhlaghpour, M.; Haley, E.; Parnell, L.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.A.; Percaccio, M.; Magallon, J.; Remedios-Chan, M.; Rosas, A.; et al. Urine Biomarkers Individually and as a Consensus Model Show High Sensitivity and Specificity for Detecting UTIs. BMC Infect Dis 2024, 24, 153, doi:10.1186/s12879-024-09044-2.

11. Parnell, L.K.D.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.A.; Haley, E.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Anderson, L.; Baunoch, D. Elevated UTI Biomarkers in Symptomatic Patients with Urine Microbial Densities of 10,000 CFU/ML Indicate a Lower Threshold for Diagnosing UTIs. MDPI 2023, 13, 1–15, doi:10.3390/diagnostics13162688.

12. 2024 WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List (WHO BPPL) Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/376776/9789240093461-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 18 March 2025).

13. Wu, Y.; Li, P.; Huang, Z.; Liu, J.; Yang, B.; Zhou, W.; Duan, F.; Wang, G.; Li, J. Four-Year Variation in Pathogen Distribution and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Urosepsis: A Single-Center Retrospective Analysis. Ther. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2024, 11, 20499361241248056, doi:10.1177/20499361241248058.

14. Parente, G.; Gargano, T.; Pavia, S.; Cordola, C.; Vastano, M.; Baccelli, F.; Gallotta, G.; Bruni, L.; Corvaglia, A.; Lima, M. Pyelonephritis in Pediatric Uropathic Patients: Differences from Community-Acquired Ones and Therapeutic Protocol Considerations. A 10-Year Single-Center Retrospective Study. Children 2021, 8, 436, doi:10.3390/children8060436.

Dr. Emery Haley is a scientific writing specialist with over ten years of experience in translational cell and molecular biology. As both a former laboratory scientist and an experienced science communicator, Dr. Haley is passionate about making complex research clear, approachable, and relevant. Their work has been published in over 10 papers and focuses on bridging the gap between the lab and real-world patient care to help drive better health outcomes.