S. agalactiae

Emery Haley, PhD, Scientific Writing Specialist

Streptococcus agalactiae

Clinical Summary

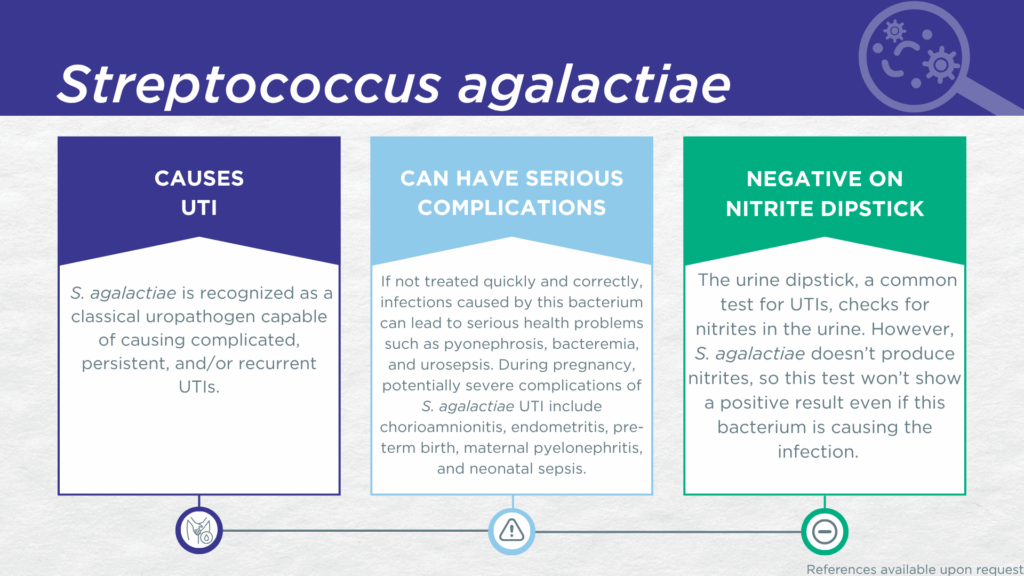

- S. agalactiae is recognized as a classical gram-positive, nitrite-negative, biofilm-forming, uropathogen.

- S. agalactiae is associated with complicated, persistent, and recurrent UTI (the same population for which the Guidance® UTI assay is indicated).

- In symptomatic UTI patients, S. agalactiae:

- Is not a contaminant (is found in catheter-collected urine specimens).

- Is viable (can grow out on culture).

- Is pathogenic (associated with elevated urine biomarkers of infection).

- Reported severe complications of S. agalactiae UTI include pyonephrosis, bacteremia, and urosepsis. During pregnancy, severe complications of S. agalactiae UTI include chorioamnionitis, endometritis, pre-term birth, maternal pyelonephritis, and neonatal sepsis.

Bacterial Characteristics

Gram-stain

Gram-positive

Morphology

Coccus

Growth Requirements

Non-fastidious (grows well in standard urine culture conditions)

Facultative anaerobe

*Note: We do not perform P-AST™ on Streptococci (including S. agalactiae). Streptococci have well-established and predictably high susceptibilities to beta-lactam antibiotics (see treatment section). Therefore, confirmation of susceptibility by P-AST™ assay is unnecessary.

Nitrate Reduction

No

Urease

Negative

Biofilm Formation

Yes

Pathogenicity

Colonizer or Pathobiont

Clinical Relevance in UTI

S. agalactiae is a biofilm-forming gram-positive microorganism typically considered to be a classical uropathogen.[1] It is the most common human pathogen within the “group B” Lancefield classification of Streptococci, and is therefore, sometimes referred to generally as “group B Strep” or GBS.

S. agalactiae may asymptomatically colonize the human gastrointestinal, oropharyngeal, and urogenital niches, however, it is also an opportunistic uropathogen capable of causing severe invasive infections. It is primarily associated with complicated UTI in older adults,[2,3] pregnant women,[4–7] people with urinary tract abnormalities,[8,9] and predisposing comorbid conditions, such as diabetes [10,11]. S. agalactiae is also reported to form intracellular bacterial communities and pyocytes in patients with recurrent UTI.[12]

Additionally, in mouse models of polymicrobial UTIs, S. agalactiae exhibits synergistic interactions with other uropathogens including increased adherence interactions with C. albicans and immune dampening resulting in persistent E. coli infection.[13]

In a study of older adult males and females with clinically suspected complicated UTI, S. agalactiae was detected in both midstream voided and in-and-out-catheter collected specimens indicating that it was truly present in the bladder, not simply a contaminant picked up during voiding.[14] Furthermore, elevated markers of immune system activation in the urinary tract have been measured from the same clinical urine specimens in which S. agalactiae was detected, indicating that the presence of S. agalactiae was associated with an immune response to urinary tract infection.[15–17] S. agalactiae lacks nitrate reductase activity, so screening strategies involving urinalysis for nitrite positivity will be false-negative.[18,19]

Severe complications of S. agalactiae UTI in pregnancy may include chorioamnionitis, endometritis, pre-term birth, maternal pyelonephritis, and neonatal sepsis.[6,7] Pyonephrosis, bacteremia, and urosepsis have also been reported as complications in non-pregnant individuals.[8,9]

Together, these findings indicate that S. agalactiae should be seriously considered as a uropathogen and demonstrate the value of detecting this organism, particularly during pregnancy, in individuals with recurrent UTI, and in individuals with urinary tract abnormalities, immune compromising comorbidities, or other risk factors for complicated UTI.

Treatment

Evidence of Efficacy (Checkmarks): Ampicillin, Cefepime, Ceftriaxone, Levofloxacin, Linezolid, Meropenem, and Vancomycin.

Because Streptococci have well-established and predictably high susceptibilities to beta-lactam antibiotics, particularly penicillin and ampicillin, confirmation of susceptibility by P-AST™ assay is unnecessary. To provide faster result reporting without compromising relevant treatment options, Pathnostics provides a report without P-AST™ for monomicrobial Streptococci. See the checkmarks for suggested treatment options.

1. Desai, D.; Goh, K.G.K.; Sullivan, M.J.; Chattopadhyay, D.; Ulett, G.C. Hemolytic Activity and Biofilm-Formation among Clinical Isolates of Group B Streptococcus Causing Acute Urinary Tract Infection and Asymptomatic Bacteriuria. Int. J. Méd. Microbiol. 2021, 311, 151520, doi:10.1016/j.ijmm.2021.151520.

2. Farley, M.M. Group B Streptococcal Infection in Older Patients. Drugs Aging 1995, 6, 293–300, doi:10.2165/00002512-199506040-00004.

3. Navarro-Torné, A.; Curcio, D.; Moïsi, J.C.; Jodar, L. Burden of Invasive Group B Streptococcus Disease in Non-Pregnant Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258030, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0258030.

4. Saghabashi, A.; Rostami, K.; Allameh, M.; Khaledi, M.; Afkhami, H.; Fathi, J.; Parvizi, R.; Esmkhani, M.; Dezfuli, A.A.Z.; Shahriary, S.; et al. Prevalence of Streptococcus Agalactiae in Urinary Tract Infections of Pregnant Women. J. Méd. Bacteriol. 2024, doi:10.18502/jmb.v12i1.15017.

5. Lusta, M.; Voronkova, O.; Finkova, O.; Moskalenko, L.; Tatianenko, M.; Shyrokykh, K.; Falko, O.; Stupak, O.; Moskalenko, T.; Sliesarenko, K. Microbiological Monitoring of Antibiotic Resistance of Strains of Streptococcus Agalactiae among Pregnant Women. Regul. Mech. Biosyst. 2023, 14, 208–212, doi:10.15421/022331.

6. Radu, V.-D.; Vicoveanu, P.; Cărăuleanu, A.; Adam, A.-M.; Melinte-Popescu, A.-S.; Adam, G.; Onofrei, P.; Socolov, D.; Vasilache, I.-A.; Harabor, A.; et al. Pregnancy Outcomes in Patients with Urosepsis and Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections—A Retrospective Study. Medicina 2023, 59, 2129, doi:10.3390/medicina59122129.

7. Sachdeva, S.; Rosett, H.A.; Krischak, M.K.; Weaver, K.E.; Heine, R.P.; Denoble, A.E.; Dotters-Katz, S.K. Urinary Tract Infection and Progression to Pyelonephritis: Group B Streptococcus versus E. Coli. Am. J. Perinatol. Rep. 2023, 14, e80–e84, doi:10.1055/s-0044-1779031.

8. Freudenstein, D.; Reinshagen, K.; Petzold, A.; Debus, A.; Schroten, H.; Tenenbaum, T. Ultra Late Onset Group B Streptococcal Sepsis with Acute Renal Failure in a Child with Urethral Obstruction: A Case Report. J. Méd. Case Rep. 2012, 6, 68, doi:10.1186/1752-1947-6-68.

9. Elmanar, R.; Atmaja, M.H.S. Imaging of Group B Streptococcus Infection in Pyonephrosis: A Case Report. Radiol. Case Rep. 2022, 17, 3302–3307, doi:10.1016/j.radcr.2022.06.014.

10. John, P.P.; Baker, B.C.; Paudel, S.; Nassour, L.; Cagle, H.; Kulkarni, R. Exposure to Moderate Glycosuria Induces Virulence of Group B Streptococcus. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 223, 843–847, doi:10.1093/infdis/jiaa443.

11. Nguyen, L.M.; Omage, J.I.; Noble, K.; McNew, K.L.; Moore, D.J.; Aronoff, D.M.; Doster, R.S. Group B Streptococcal Infection of the Genitourinary Tract in Pregnant and Non‐pregnant Patients with Diabetes Mellitus: An Immunocompromised Host or Something More? Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2021, 86, e13501, doi:10.1111/aji.13501.

12. Barrios-Villa, E.; Mendez-Pfeiffer, P.; Valencia, D.; Caporal-Hernandez, L.; Ballesteros-Monrreal, M.G. Intracellular Bacterial Communities in Patient with Recurrent Urinary Tract Infection Caused by Staphylococcus Spp and Streptococcus Agalactiae: A Case Report and Literature Review. Afr. J. Urol. 2022, 28, 46, doi:10.1186/s12301-022-00314-6.

13. Gaston, J.R.; Johnson, A.O.; Bair, K.L.; White, A.N.; Armbruster, C.E. Polymicrobial Interactions in the Urinary Tract: Is the Enemy of My Enemy My Friend? Infect Immun 2021, 89, doi:10.1128/iai.00652-20.

14. Wang, D.; Haley, E.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.; Zhao, X.; Anderson, L.A.; Allison, J.L.; Stebbins, K.L.; Diaz, M.J.; et al. Emerging and Fastidious Uropathogens Were Detected by M-PCR with Similar Prevalence and Cell Density in Catheter and Midstream Voided Urine Indicating the Importance of These Microbes in Causing UTIs. Infect. Drug Resist. 2023, Volume 16, 7775–7795, doi:10.2147/idr.s429990.

15. Haley, E.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.A.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Anderson, L.A.; Baunoch, D. The Prevalence and Association of Different Uropathogens Detected by M-PCR with Infection-Associated Urine Biomarkers in Urinary Tract Infections. Res. Rep. Urol. 2024, 16, 19–29, doi:10.2147/rru.s443361.

16. Akhlaghpour, M.; Haley, E.; Parnell, L.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.A.; Percaccio, M.; Magallon, J.; Remedios-Chan, M.; Rosas, A.; et al. Urine Biomarkers Individually and as a Consensus Model Show High Sensitivity and Specificity for Detecting UTIs. BMC Infect Dis 2024, 24, 153, doi:10.1186/s12879-024-09044-2.

17. Parnell, L.K.D.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.A.; Haley, E.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Anderson, L.; Baunoch, D. Elevated UTI Biomarkers in Symptomatic Patients with Urine Microbial Densities of 10,000 CFU/ML Indicate a Lower Threshold for Diagnosing UTIs. MDPI 2023, 13, 1–15, doi:10.3390/diagnostics13162688.

18. BacDive | The Bacterial Diversity Metadatabase Available online: https://bacdive.dsmz.de/ (accessed on 11 February 2025).

19. BioCyc Pathway/Genome Database Collection Available online: https://biocyc.org/ (accessed on 11 February 2025).

Dr. Emery Haley is a scientific writing specialist with over ten years of experience in translational cell and molecular biology. As both a former laboratory scientist and an experienced science communicator, Dr. Haley is passionate about making complex research clear, approachable, and relevant. Their work has been published in over 10 papers and focuses on bridging the gap between the lab and real-world patient care to help drive better health outcomes.