S. aureus

Emery Haley, PhD, Scientific Writing Specialist

Staphylococcus aureus

Clinical Summary

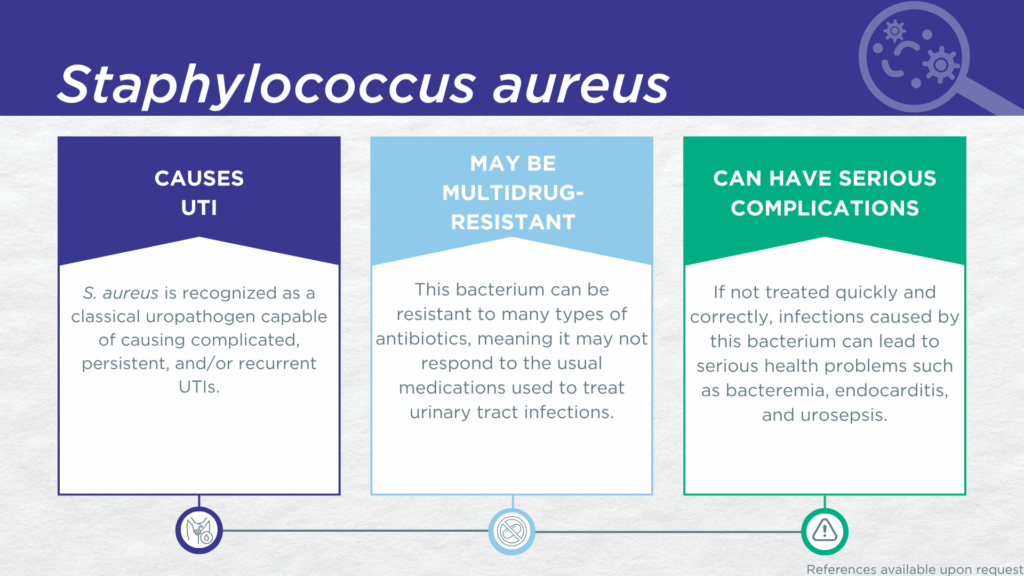

- S. aureus is recognized as a classical gram-positive, urease-positive, biofilm-forming uropathogen.

- S. aureus is associated with complicated, persistent, and recurrent UTI (the same population for which the Guidance® UTI assay is indicated).

- In symptomatic UTI patients, S. aureus:

- Is not a contaminant (is found in catheter-collected urine specimens).

- Is viable (can grow out on culture).

- Is pathogenic (associated with elevated urine biomarkers of infection).

- Reported severe complications of S. aureus UTI include bacteremia, endocarditis, and urosepsis.

- Multidrug-resistant aureus (including MRSA) is an “ESKAPE” pathogen and a well-studied significant global health threat.

- Note: Pathnostics offers a MRSA-phenotype add-on reflex assay.

Bacterial Characteristics

Gram-stain

Gram-positive

Morphology

Coccus

Growth Requirements

Non-fastidious (grows well in standard urine culture conditions)

Facultative anaerobe

Nitrate Reduction

Yes

Urease

Positive

Biofilm Formation

Yes

Pathogenicity

Colonizer or Pathobiont

Clinical Relevance in UTI

S. aureus is a urease-positive microorganism[1] typically considered to be a classical uropathogen.[2,3] Though rarely detected in acute uncomplicated UTI, S. aureus is commonly reported in complicated,[4–9] persistent,[10] and recurrent [11,12] UTIs.[13] S. aureus is also well-known for forming biofilms in polymicrobial catheter-associated complicated UTIs.[14–17] S. aureus has been reported to exhibit synergism with Candida albicans and to be antagonized by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in polymicrobial UTIs.[18]

A study utilizing next-generation sequencing (NGS) on urine specimens obtained by transurethral catheterization found that S. aureus was commonly detected in adult female patients with recurrent UTI, specifically.[11] In another study of older adult males and females with clinically suspected complicated UTI, S. aureus was detected via multiplex polymerase chain reaction (M-PCR) in both midstream voided and in-and-out-catheter collected specimens.[7] These studies using catheter-obtained urine specimens demonstrate that S. aureus is truly present in the bladder of patients with complicated or recurrent UTI and is not simply a contaminant picked up during voiding. Yet another cross-sectional study of paired urine samples obtained by transurethral catheterization and midstream voided urine from adult females with recurrent UTIs, expanded quantitative urine culture (EQUC) grew viable S. aureus colonies from several catheter-collected specimens.[12] This finding demonstrates that the S. aureus in the bladder of recurrent UTI patients is viable, and not simply an artifact of molecular detection methods, such as M-PCR and NGS. Furthermore, elevated markers of immune system activation in the urinary tract have been measured from the same clinical urine specimens in which

S. aureus was detected, indicating that the presence of S. aureus was associated with an immune response to urinary tract infection.[8,19,20]

S. aureus is one of the six so-called “ESKAPE pathogens” identified as critical multi-drug resistant bacteria requiring urgent development of effective therapeutics.[21] Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA),[22,23] Vancomycin-Intermediate S. aureus (VISA),[24] Vancomycin-heteroresistant S. aureus (hVISA),[25] and Vancomycin-Resistant

S. aureus (VRSA)[9] are increasingly dire global health threats. Rapid detection and appropriate treatment of S. aureus UTI, especially MRSA UTI, is essential for reducing morbidity and mortality associated with bacteremia, endocarditis, and urosepsis originating from the urinary tract.[5,26–28]

Together, these findings indicate that S. aureus should be seriously considered as a uropathogen and demonstrate the value of detecting this organism, particularly in individuals with recurrent UTI and/or indwelling catheters or other risk factors for complicated UTI.

Note: An add-on reflex test option for a MRSA phenotype assay can be selected on the Pathnostics test requisition form. If this option is selected and the Guidance® UTI assay detects both S. aureus and the mecA gene, a colorimetric assay to confirm the MRSA phenotype is performed. This phenotypic test result is essential to optimize treatment, because resistance gene can be inactivated, and may not always result in phenotypic resistance, even when present and detected.[29] In such cases, having a negative MRSA phenotype result enables the clinician to pursue less aggressive antibiotic treatment options. In contrast, if the assay confirms phenotypic methicillin resistance, more aggressive treatment of the MRSA infection is indicated.

Treatment

Evidence of Efficacy (Checkmarks): Doxycycline, Gentamicin, Linezolid, Nitrofurantoin, Sulfamethoxazole/Trimethoprim, Trimethoprim, and Vancomycin.

1. BacDive | The Bacterial Diversity Metadatabase Available online: https://bacdive.dsmz.de/ (accessed on 11 February 2025).

2. Moreland, R.B.; Brubaker, L.; Tinawi, L.; Wolfe, A.J. Rapid and Accurate Testing for Urinary Tract Infection: New Clothes for the Emperor. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2024, e0012924, doi:10.1128/cmr.00129-24.

3. Brubaker, L.; Chai, T.C.; Horsley, H.; Khasriya, R.; Moreland, R.B.; Wolfe, A.J. Tarnished Gold—the “Standard” Urine Culture: Reassessing the Characteristics of a Criterion Standard for Detecting Urinary Microbes. Front. Urol. 2023, 3, 1206046, doi:10.3389/fruro.2023.1206046.

4. Saenkham-Huntsinger, P.; Hyre, A.N.; Hanson, B.S.; Donati, G.L.; Adams, L.G.; Ryan, C.; Londoño, A.; Moustafa, A.M.; Planet, P.J.; Subashchandrabose, S. Copper Resistance Promotes Fitness of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus during Urinary Tract Infection. mBio 2021, 12, 10.1128/mbio.02038-21, doi:10.1128/mbio.02038-21.

5. Muder, R.R.; Brennen, C.; Rihs, J.D.; Wagener, M.M.; Obman, A.; Stout, J.E.; Yu, V.L. Isolation of Staphylococcus Aureus from the Urinary Tract: Association of Isolation with Symptomatic Urinary Tract Infection and Subsequent Staphylococcal Bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis 2006, 42, 46–50, doi:10.1086/498518.

6. Zubair, K.U.; Shah, A.H.; Fawwad, A.; Sabir, R.; Butt, A. Frequency of Urinary Tract Infection and Antibiotic Sensitivity of Uropathogens in Patients with Diabetes. Pak. J. Méd. Sci. 2019, 35, 1664–1668, doi:10.12669/pjms.35.6.115.

7. Wang, D.; Haley, E.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.; Zhao, X.; Anderson, L.A.; Allison, J.L.; Stebbins, K.L.; Diaz, M.J.; et al. Emerging and Fastidious Uropathogens Were Detected by M-PCR with Similar Prevalence and Cell Density in Catheter and Midstream Voided Urine Indicating the Importance of These Microbes in Causing UTIs. Infect. Drug Resist. 2023, Volume 16, 7775–7795, doi:10.2147/idr.s429990.

8. Haley, E.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.A.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Anderson, L.A.; Baunoch, D. The Prevalence and Association of Different Uropathogens Detected by M-PCR with Infection-Associated Urine Biomarkers in Urinary Tract Infections. Res. Rep. Urol. 2024, 16, 19–29, doi:10.2147/rru.s443361.

9. Selim, S.; Faried, O.A.; Almuhayawi, M.S.; Saleh, F.M.; Sharaf, M.; Nahhas, N.E.; Warrad, M. Incidence of Vancomycin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Strains among Patients with Urinary Tract Infections. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 408, doi:10.3390/antibiotics11030408.

10. Xu, K.; Wang, Y.; Jian, Y.; Chen, T.; Liu, Q.; Wang, H.; Li, M.; He, L. Staphylococcus Aureus ST1 Promotes Persistent Urinary Tract Infection by Highly Expressing the Urease. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1101754, doi:10.3389/fmicb.2023.1101754.

11. Yoo, J.-J.; Shin, H.B.; Song, J.S.; Kim, M.; Yun, J.; Kim, Z.; Lee, Y.M.; Lee, S.W.; Lee, K.W.; Kim, W.B.; et al. Urinary Microbiome Characteristics in Female Patients with Acute Uncomplicated Cystitis and Recurrent Cystitis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1097, doi:10.3390/jcm10051097.

12. Hochstedler, B.R.; Burnett, L.; Price, T.K.; Jung, C.; Wolfe, A.J.; Brubaker, L. Urinary Microbiota of Women with Recurrent Urinary Tract Infection: Collection and Culture Methods. Int Urogynecol J 2022, 33, 563–570, doi:10.1007/s00192-021-04780-4.

13. Mason, C.Y.; Sobti, A.; Goodman, A.L. Staphylococcus Aureus Bacteriuria: Implications and Management. JAC-Antimicrob. Resist. 2023, 5, dlac123, doi:10.1093/jacamr/dlac123.

14. Thorn, D.J.; Wolfe, V.; Inder, P.; Lin, V.W.-H. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus in Patients with Spinal Cord Injury. J. Spinal Cord Med. 1999, 22, 125–131, doi:10.1080/10790268.1999.11719558.

15. Carvalho, F.M.; Mergulhão, F.J.M.; Gomes, L.C. Using Lactobacilli to Fight Escherichia Coli and Staphylococcus Aureus Biofilms on Urinary Tract Devices. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1525, doi:10.3390/antibiotics10121525.

16. Stewart, E.; Hochstedler-Kramer, B.R.; Khemmani, M.; Clark, N.M.; Parada, J.P.; Farooq, A.; Doshi, C.; Wolfe, A.J.; Albarillo, F.S. Characterizing the Urobiome in Geriatric Males with Chronic Indwelling Urinary Catheters: An Exploratory Longitudinal Study. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e00941-24, doi:10.1128/spectrum.00941-24.

17. Walker, J.N.; Flores-Mireles, A.L.; Pinkner, C.L.; Schreiber, H.L.; Joens, M.S.; Park, A.M.; Potretzke, A.M.; Bauman, T.M.; Pinkner, J.S.; Fitzpatrick, J.A.J.; et al. Catheterization Alters Bladder Ecology to Potentiate Staphylococcus Aureus Infection of the Urinary Tract. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017, 114, E8721–E8730, doi:10.1073/pnas.1707572114.

18. Gaston, J.R.; Johnson, A.O.; Bair, K.L.; White, A.N.; Armbruster, C.E. Polymicrobial Interactions in the Urinary Tract: Is the Enemy of My Enemy My Friend? Infect Immun 2021, 89, doi:10.1128/iai.00652-20.

19. Akhlaghpour, M.; Haley, E.; Parnell, L.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.A.; Percaccio, M.; Magallon, J.; Remedios-Chan, M.; Rosas, A.; et al. Urine Biomarkers Individually and as a Consensus Model Show High Sensitivity and Specificity for Detecting UTIs. BMC Infect Dis 2024, 24, 153, doi:10.1186/s12879-024-09044-2.

20. Parnell, L.K.D.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.A.; Haley, E.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Anderson, L.; Baunoch, D. Elevated UTI Biomarkers in Symptomatic Patients with Urine Microbial Densities of 10,000 CFU/ML Indicate a Lower Threshold for Diagnosing UTIs. MDPI 2023, 13, 1–15, doi:10.3390/diagnostics13162688.

21. Miller, W.R.; Arias, C.A. ESKAPE Pathogens: Antimicrobial Resistance, Epidemiology, Clinical Impact and Therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 598–616, doi:10.1038/s41579-024-01054-w.

22. Sasirekha, B. Prevalence of ESBL, AmpC β-Lactamases and MRSA among Uropathogens and Its Antibiogram. EXCLI J. 2012, 12, 81–88.

23. Gajdács, M.; Ábrók, M.; Lázár, A.; Burián, K. Increasing Relevance of Gram-Positive Cocci in Urinary Tract Infections: A 10-Year Analysis of Their Prevalence and Resistance Trends. Sci Rep-uk 2020, 10, 17658, doi:10.1038/s41598-020-74834-y.

24. Park, J.W.; Lee, H.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, B. Characterization of Infections with Vancomycin-Intermediate Staphylococcus Aureus (VISA) and Staphylococcus Aureus with Reduced Vancomycin Susceptibility in South Korea. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6236, doi:10.1038/s41598-019-42307-6.

25. PM, Y.D.P. Challenges in the Laboratory Diagnosis and Clinical Management of Heteroresistant Vancomycin Staphylococcus Aureus (HVISA). Clin. Microbiol.: Open Access 2015, 2015, doi:10.4172/2327-5073.1000214.

26. Mohajer, M.A.; Musher, D.M.; Minard, C.G.; Darouiche, R.O. Clinical Significance of Staphylococcus Aureus Bacteriuria at a Tertiary Care Hospital. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 45, 688–695, doi:10.3109/00365548.2013.803291.

27. Mylotte, J.M.; Tayara, A.; Goodnough, S. Epidemiology of Bloodstream Infection in Nursing Home Residents: Evaluation in a Large Cohort from Multiple Homes. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 35, 1484–1490, doi:10.1086/344649.

28. Lafon, T.; Padilla, A.C.H.; Baisse, A.; Lavaud, L.; Goudelin, M.; Barraud, O.; Daix, T.; Francois, B.; Vignon, P. Community-Acquired Staphylococcus Aureus Bacteriuria: A Warning Microbiological Marker for Infective Endocarditis? BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 504, doi:10.1186/s12879-019-4106-0.

29. Pereira, C.; Larsson, J.; Hjort, K.; Elf, J.; Andersson, D.I. The Highly Dynamic Nature of Bacterial Heteroresistance Impairs Its Clinical Detection. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 521, doi:10.1038/s42003-021-02052-x.

Dr. Emery Haley is a scientific writing specialist with over ten years of experience in translational cell and molecular biology. As both a former laboratory scientist and an experienced science communicator, Dr. Haley is passionate about making complex research clear, approachable, and relevant. Their work has been published in over 10 papers and focuses on bridging the gap between the lab and real-world patient care to help drive better health outcomes.