U. urealyticum

Emery Haley, PhD, Scientific Writing Specialist

Ureaplasma urealyticum

Clinical Summary

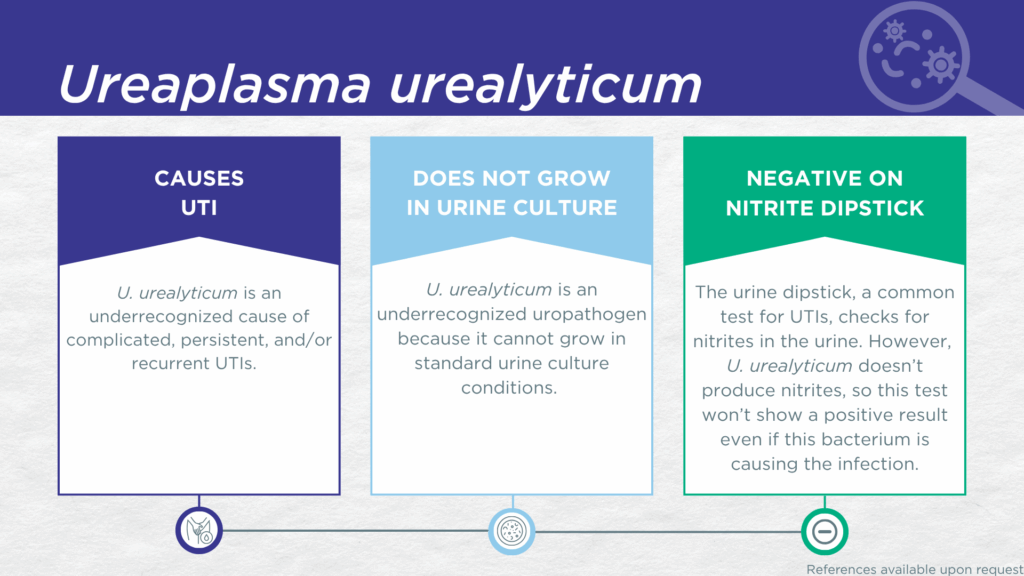

- U. urealyticum is a nitrite-negative, urease-positive, biofilm-forming microorganism lacking a cell wall.

- U. urealyticum is fastidious and cannot grow in standard urine culture conditions.

- U. urealyticum is associated with complicated, persistent, and recurrent UTIs.

- In symptomatic UTI patients, U. urealyticum:

- Is not a contaminant (is found in catheter-collected urine specimens).

- Is pathogenic (associated with elevated urine biomarkers of infection).

Bacterial Characteristics

Gram-stain

Not Applicable (Ureaplasma species do not have a cell wall)

Morphology

Not Applicable (Ureaplasma species do not have a cell wall)

Growth Requirements

Fastidious (slow growing, prefers a pH of 6.0-7.0 & 5% CO2, and requires specific nutrients including urea)

Facultative anaerobe

Nitrate Reduction

No

Urease

Positive

Biofilm Formation

Yes

Pathogenicity

Colonizer or Pathobiont

Clinical Relevance in UTI

This fastidious organism has been considered a colonizer of the urogenital microbiome and is indeed detected in some asymptomatic individuals.[1–3] Clinically, U. urealyticum is most commonly implicated in preterm labor/birth,[4] miscarriage,[5] stillbirth,[6] and intraamniotic infection,[7] as well as bacterial vaginosis (BV) [8]. However, U. urealyticum has also been reported as a causative organism in UTI and pyelonephritis in immunocompromised individuals and kidney transplant recipients.[11–13] It has been detected in men with culture-negative prostatitis [14] or epididymitis,[15] in urinary stones,[16] in the urine of women with unexplained lower urinary tract symptoms improved by azithromycin and/or doxycycline treatment,[17–20] and in the urine of women with UTI symptoms and “sterile” pyuria [3,21]. Even in young otherwise healthy women, U. urealyticum is frequently found in polymicrobial UTIs, where it may persist and contribute to treatment failure despite the fact that a more commonly recognized uropathogen may have been the primary source of the original UTI symptoms.[3,22]

U. urealyticum UTI is an easily missed diagnosis. Firstly, U. urealyticum lacks nitrate reductase activity, so screening strategies involving urinalysis for nitrite positivity will be false-negative.[9,10] Secondly, U. urealyticum is rarely identified in clinical laboratories performing standard culture techniques for UTI diagnosis, because its lack of a cell wall structure prevents the effective use of gram-staining and morphology analyses.[11] Instead, U. urealyticum UTI is most often diagnosed by advanced molecular techniques, including polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and sequencing.[11]

In a study of older adult males and females with clinically suspected complicated UTI, U. urealyticum was detected in both midstream voided and in-and-out-catheter collected specimens indicating that it was truly present in the bladder, not simply a contaminant picked up during voiding.[23] Furthermore, elevated markers of immune system activation in the urinary tract have been measured from the same clinical urine specimens in which U. urealyticum was detected, indicating that the presence of U. urealyticum was associated with an immune response to urinary tract infection.[24–26]

Together, these findings indicate that U. urealyticum should be seriously considered as a uropathogen and demonstrate the value of detecting this organism, particularly in women with chronic or recurrent UTI symptoms and pyuria with a negative standard urine culture.

Note: The primers utilized in the Guidance® assays for U. urealyticum are reported to cross-detect U. parvum due to the genomic similarities between these two recently disambiguated species.[27] Prior to the year 2000, Ureaplasma parvum (U. parvum) was not a recognized species.[28] Instead, it was considered a biovar of the U. urealyticum species (a variant strain that differs physiologically or biochemically from other strains within a particular species). Specifically, what is now U. parvum was called U. urealyticum Biovar 1, but most studies referred to U. urealyticum without specifying biovars. Furthermore, even literature published after 2000 often combines and/or conflates these two species of Ureaplasma, such as by simply reporting “Ureaplasma species”. One study found that U. parvum (previously U. urealyticum biovar 1) was primarily detected in asymptomatic individuals, whereas U. urealyticum (previously U. urealyticum biovar 2) was primarily detected in individuals with symptomatic genitourinary infections and was associated with higher resistance to multiple classes of antibiotics, including macrolides and fluoroquinolones.[29] However, most of the limited number of reports that specifically examine the U. parvum species suggest that U. parvum has similar associations with lower urinary tract symptoms/’sterile’ pyuria as those reported for U. urealyticum.[22,30,31]

Treatment

The lack of a cell wall in U. urealyticum makes the organism inherently resistant to antibiotics whose mechanism of action targets cell wall components. Therefore, U. urealyticum is intrinsically resistant to all beta-lactam antibiotics (including penicillins, cephalosporins, monobactams, and carbapenems) and to vancomycin.

Evidence of Efficacy (Checkmarks): Doxycycline and Levofloxacin.

1. Ezeanya-Bakpa, C.C.; Agbakoba, N.R.; Oguejiofor, C.B.; Enweani-Nwokelo, I.B. Sequence Analysis Reveals Asymptomatic Infection with Mycoplasma Hominis and Ureaplasma Urealyticum Possibly Leads to Infertility in Females: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Reprod. Biomed. 2021, 19, 951–958, doi:10.18502/ijrm.v19i11.9910.

2. Cutoiu, A.; Boda, D. Prevalence of Ureaplasma Urealyticum, Mycoplasma Hominis and Chlamydia Trachomatis in Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Patients. Biomed. Rep. 2023, 19, 74, doi:10.3892/br.2023.1656.

3. Elkolaly, N.M.E.; Amin, A.M.; Mohamed, M.Z.E.; Abd-Elmonsef, M.M.E. Rapid Detection of Urinary Ureaplasma Urealyticum and Mycoplasma Hominis Isolated from Pregnant Women and Their Antibiotic Susceptibility Profile. Infect Dis Clin Prac 2021, 29, e395–e400, doi:10.1097/ipc.0000000000001044.

4. Miyoshi, Y.; Suga, S.; Sugimi, S.; Kurata, N.; Yamashita, H.; Yasuhi, I. Vaginal Ureaplasma Urealyticum or Mycoplasma Hominis and Preterm Delivery in Women with Threatened Preterm Labor. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022, 35, 878–883, doi:10.1080/14767058.2020.1733517.

5. Oliveira, M.T.S.; Oliveira, C.N.T.; Silva, L.S.C. da; Oliveira, H.B.M.; Freire, R.S.; Marques, L.M.; Santos, M.L.C.; Melo, F.F. de; Souza, C.L.; Oliveira, M.V. Relationship between Mollicutes and Spontaneous Abortion: An Epidemiological Analysis. World J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 10, 1–15, doi:10.5317/wjog.v10.i1.1.

6. Gabrielli, L.; Pavoni, M.; Monari, F.; Pillastrini, F.B.; Bonasoni, M.P.; Locatelli, C.; Bisulli, M.; Vancini, A.; Cataneo, I.; Ortalli, M.; et al. Infection-Related Stillbirths: A Detailed Examination of a Nine-Year Multidisciplinary Study. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 71, doi:10.3390/microorganisms13010071.

7. Oh, K.J.; Lee, K.A.; Sohn, Y.-K.; Park, C.-W.; Hong, J.-S.; Romero, R.; Yoon, B.H. Intraamniotic Infection with Genital Mycoplasmas Exhibits a More Intense Inflammatory Response than Intraamniotic Infection with Other Microorganisms in Patients with Preterm Premature Rupture of Membranes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 203, 211.e1-211.e8, doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2010.03.035.

8. ROSENSTEIN, I.J.; MORGAN, D.J.; SHEEHAN, M.; LAMONT, R.F.; TAYLOR-ROBINSON, D. Bacterial Vaginosis in Pregnancy: Distribution of Bacterial Species in Different Gram-Stain Categories of the Vaginal Flora. J. Méd. Microbiol. 1996, 45, 120–126, doi:10.1099/00222615-45-2-120.

9. BacDive | The Bacterial Diversity Metadatabase Available online: https://bacdive.dsmz.de/ (accessed on 11 February 2025).

10. BioCyc Pathway/Genome Database Collection Available online: https://biocyc.org/ (accessed on 11 February 2025).

11. Shrestha, M.; Nair, D.P.J.R.; Amin, S.; Pokhrel, A.; Munankami, S. Unveiling Ureaplasma: A Case Report of a Rare Culprit in Pyelonephritis. Cureus 2024, 16, e54958, doi:10.7759/cureus.54958.

12. Schwartz, D.J.; Elward, A.; Storch, G.A.; Rosen, D.A. Ureaplasma Urealyticum Pyelonephritis Presenting with Progressive Dysuria, Renal Failure, and Neurologic Symptoms in an Immunocompromised Patient. Transpl Infect Dis 2019, 21, e13032, doi:10.1111/tid.13032.

13. Fernández, M.L.S.; Cano, N.R.; Santamarta, L.Á.; Fraile, M.G.; Blake, O.; Corte, C.D. A Current Review of the Etiology, Clinical Features, and Diagnosis of Urinary Tract Infection in Renal Transplant Patients. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1456, doi:10.3390/diagnostics11081456.

14. Karami, A.A.; Javadi, A.; Salehi, S.; Nasirian, N.; Maali, A.; Shadkam, M.B.; Najari, M.; Rousta, Z.; Alizadeh, S.A. Detection of Bacterial Agents Causing Prostate Infection by Culture and Molecular Methods from Biopsy Specimens. Iran. J. Microbiol. 2022, 14, 161–167, doi:10.18502/ijm.v14i2.9182.

15. Ito, S.; Tsuchiya, T.; Yasuda, M.; Yokoi, S.; Nakano, M.; Deguchi, T. Prevalence of Genital Mycoplasmas and Ureaplasmas in Men Younger than 40 Years‐of‐age with Acute Epididymitis. Int. J. Urol. 2012, 19, 234–238, doi:10.1111/j.1442-2042.2011.02917.x.

16. Smolec, D.; Poland, D. of M.M., Faculty of Medical Sciences in Katowice, Medical University of Silesia, Katowice,; Gofron, Z.; Poland, M.H.E.M.S.H., Katowice,; Ekiel, A. Urolithiasis – Do Ureaplasmas Play a Role in Etiology. Iran. J. Méd. Microbiol. 2023, 17, 369–372, doi:10.30699/ijmm.17.3.369.

17. Baka, S.; Kouskouni, E.; Antonopoulou, S.; Sioutis, D.; Papakonstantinou, M.; Hassiakos, D.; Logothetis, E.; Liapis, A. Prevalence of Ureaplasma Urealyticum and Mycoplasma Hominis in Women With Chronic Urinary Symptoms. Urology 2009, 74, 62–66, doi:10.1016/j.urology.2009.02.014.

18. Humburg, J.; Frei, R.; Wight, E.; Troeger, C. Accuracy of Urethral Swab and Urine Analysis for the Detection of Mycoplasma Hominis and Ureaplasma Urealyticum in Women with Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2012, 285, 1049–1053, doi:10.1007/s00404-011-2109-1.

19. Latthe, P.; Toozs-Hobson, P.; Gray, J. Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma Colonisation in Women with Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. J Obstet Gynaecol 2009, 28, 519–521, doi:10.1080/01443610802097690.

20. Crescenze, I.; Shah, P.; Adams, G.; Cameron, A.P.; Stoffel, J.; Romo, P.B.; Gupta, P.; Clemens, Q. MP15-05 TREATMENT OUTCOMES OF UREAPLASMA AND MYCOPLASMA SPECIES ISOLATED FROM PATIENTS WITH PAIN AND LOWER URINARY TRACT SYMPTOMS. J. Urol. 2018, 199, e190, doi:10.1016/j.juro.2018.02.518.

21. Nassar, F.; Abu-Elamreen, F.; Shubair, M.; Sharif, F. Detection of Chlamydia Trachomatis and Mycoplasma Hominis, Genitalium and Ureaplasma Urealyticum by Polymerase Chain Reaction in Patients with Sterile Pyuria. Adv Med Sci 2008, 53, 80–86, doi:10.2478/v10039-008-0020-1.

22. Valentine-King, M.A.; Brown, M.B. Antibacterial Resistance in Ureaplasma Species and Mycoplasma Hominis Isolates from Urine Cultures in College-Aged Females. Antimicrob Agents Ch 2017, 61, doi:10.1128/aac.01104-17.

23. Wang, D.; Haley, E.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.; Zhao, X.; Anderson, L.A.; Allison, J.L.; Stebbins, K.L.; Diaz, M.J.; et al. Emerging and Fastidious Uropathogens Were Detected by M-PCR with Similar Prevalence and Cell Density in Catheter and Midstream Voided Urine Indicating the Importance of These Microbes in Causing UTIs. Infect. Drug Resist. 2023, Volume 16, 7775–7795, doi:10.2147/idr.s429990.

24. Haley, E.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.A.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Anderson, L.A.; Baunoch, D. The Prevalence and Association of Different Uropathogens Detected by M-PCR with Infection-Associated Urine Biomarkers in Urinary Tract Infections. Res. Rep. Urol. 2024, 16, 19–29, doi:10.2147/rru.s443361.

25. Akhlaghpour, M.; Haley, E.; Parnell, L.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.A.; Percaccio, M.; Magallon, J.; Remedios-Chan, M.; Rosas, A.; et al. Urine Biomarkers Individually and as a Consensus Model Show High Sensitivity and Specificity for Detecting UTIs. BMC Infect Dis 2024, 24, 153, doi:10.1186/s12879-024-09044-2.

26. Parnell, L.K.D.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.A.; Haley, E.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Anderson, L.; Baunoch, D. Elevated UTI Biomarkers in Symptomatic Patients with Urine Microbial Densities of 10,000 CFU/ML Indicate a Lower Threshold for Diagnosing UTIs. MDPI 2023, 13, 1–15, doi:10.3390/diagnostics13162688.

27. TaqMan Microbe Detection Assays U Urealyticum Available online: https://www.thermofisher.com/microbe-detection/taqman/query/Ba04646254_s1 (accessed on 17 February 2025).

28. Kong, F.; Ma, Z.; James, G.; Gordon, S.; Gilbert, G.L. Species Identification and Subtyping OfUreaplasma Parvum and Ureaplasma UrealyticumUsing PCR-Based Assays. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2000, 38, 1175–1179, doi:10.1128/jcm.38.3.1175-1179.2000.

29. Zhu, C.; Hu, Z.; Dong, C.; Zhang, C.; Wan, M.; Ling, Y. Investigation of Ureaplasma Urealyticum Biovars and Their Relationship with Antimicrobial Resistance. Indian J. Méd. Microbiol. 2011, 29, 288–292, doi:10.4103/0255-0857.83915.

30. MAEDA, S.; DEGUCHI, T.; ISHIKO, H.; MATSUMOTO, T.; NAITO, S.; KUMON, H.; TSUKAMOTO, T.; ONODERA, S.; KAMIDONO, S. Detection of Mycoplasma Genitalium, Mycoplasma Hominis, Ureaplasma Parvum (Biovar 1) and Ureaplasma Urealyticum (Biovar 2) in Patients with Non‐gonococcal Urethritis Using Polymerase Chain Reaction‐microtiter Plate Hybridization. Int J Urol 2004, 11, 750–754, doi:10.1111/j.1442-2042.2004.00887.x.

31. Kim, M.S.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, T.J.; Oh, J.J.; Rhee, S.R.; Park, D.S.; Yu, Y.D. The Role of Ureaplasma Parvum Serovar-3 or Serovar-14 Infection in Female Patients with Chronic Micturition Urethral Pain and Recurrent Microscopic Hematuria. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2020, 10, 9608–9108, doi:10.21037/tau-20-920.

Dr. Emery Haley is a scientific writing specialist with over ten years of experience in translational cell and molecular biology. As both a former laboratory scientist and an experienced science communicator, Dr. Haley is passionate about making complex research clear, approachable, and relevant. Their work has been published in over 10 papers and focuses on bridging the gap between the lab and real-world patient care to help drive better health outcomes.