E. coli

Emery Haley, PhD, Scientific Writing Specialist

Escherichia coli

Clinical Summary

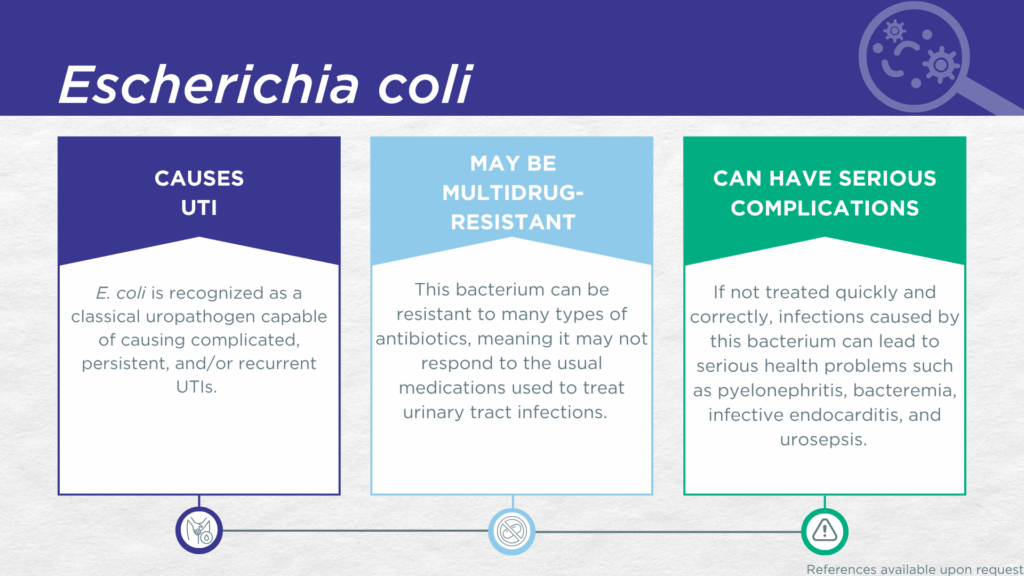

- E. coli is a gram-negative, biofilm-forming, motile bacillus classically recognized as the primary uropathogen causing UTIs.

- E. coli is associated with all types of UTIs, from acute uncomplicated cystitis to complicated, catheter-associated, and hospital-acquired UTIs with life-threatening complications, in adults and children.

- In symptomatic UTI patients, E. coli:

- Is not a contaminant (is found in catheter-collected urine specimens).

- Is viable (can grow out on culture).

- Is pathogenic (associated with elevated urine biomarkers of infection).

- Reported severe complications of E. coli UTI include pyelonephritis, bacteremia, infective endocarditis, urosepsis, and death.

- Multidrug-resistant E. coli is a significant and global health threat.

Bacterial Characteristics

Gram-stain

Gram-negative

Morphology

Bacillus

Growth Requirements

Non-fastidious (grows well in standard urine culture conditions)

Facultative anaerobe

Nitrate Reduction

Yes

Urease

Negative

Biofilm Formation

Yes

Pathogenicity

Colonizer or Pathobiont

Clinical Relevance in UTI

E. coli is a gram-negative, biofilm-forming, motile bacillus classically recognized as the primary uropathogen responsible for most UTIs. E. coli is associated with all types of UTIs, from acute uncomplicated cystitis to complicated, catheter-associated, and hospital-acquired UTIs with life-threatening complications, in adults and children.[1,2]

In preclinical models of UTI, E. coli has been shown to form biofilms, subpopulations of dormant persister cells,[3] and intracellular bacterial reservoirs within epithelial cells of the urinary tract,[4,5] abilities presumed to underlie persistent and recurrent UTIs.[6] For example, transurethral exposure of bladder cells to G. vaginalis triggers immune activation, urothelial exfoliation, and recurrent UTI due to the emergence of uropathogenic E. coli from bladder reservoirs.[7,8] More broadly speaking, in polymicrobial UTI models, E. coli exhibits both synergistic and antagonistic interactions with other uropathogenic species, including Enterococcus species, C. albicans, K. pneumoniae, M. morganii, P. aeruginosa, P. mirabilis, P. stuartii, and S. agalactiae.[1]

In a study of older adult males and females with clinically suspected complicated UTI, E. coli was detected in both midstream voided and in-and-out-catheter collected specimens indicating that it was truly present in the bladder, not simply a contaminant picked up during voiding.[9] Furthermore, elevated markers of immune system activation in the urinary tract have been measured from the same clinical urine specimens in which E. coli was detected, indicating that the presence of E. coli was associated with an immune response to urinary tract infection.[10–12]

Although not considered one of the six highest priority “ESKAPE” pathogens, The World Health Organization (WHO) has included this organism in the 2024 Bacterial Priority Pathogens List (BPPL).[13] Severe reported complications of E. coli UTI include pyelonephritis, [14,15] bacteremia, infective endocarditis,[16–19] urosepsis and death [20,21]. The tendency of this organism to travel up the urinary tract toward the kidney results in a significant risk for progression to pyelonephritis and potentially bacteriuria.[15] Indeed, due to the high prevalence of E. coli UTIs, E. coli is also the number one cause of urosepsis, [20,21] which accounts for about 25% of sepsis cases overall.

Together, these findings indicate that E. coli should be seriously considered as a uropathogen and demonstrate the value of detecting this organism in any individual with symptoms of UTI.

Treatment

Evidence of Efficacy (Checkmarks): Amoxicillin/Clavulanate, Ampicillin, Ampicillin/Sulbactam, Cefaclor, Cefazolin, Cefepime, Cefepime/Enmetazobactam, Cephalexin, Ceftazidime, Ceftriaxone, Ciprofloxacin, Doxycycline, Fosfomycin, Gentamicin, Levofloxacin, Meropenem, Nitrofurantoin, Piperacillin/Tazobactam, Sulfamethoxazole/Trimethoprim, and Trimethoprim.

1. Gaston, J.R.; Johnson, A.O.; Bair, K.L.; White, A.N.; Armbruster, C.E. Polymicrobial Interactions in the Urinary Tract: Is the Enemy of My Enemy My Friend? Infect Immun 2021, 89, doi:10.1128/iai.00652-20.

2. Yoo, J.-J.; Shin, H.B.; Song, J.S.; Kim, M.; Yun, J.; Kim, Z.; Lee, Y.M.; Lee, S.W.; Lee, K.W.; Kim, W.B.; et al. Urinary Microbiome Characteristics in Female Patients with Acute Uncomplicated Cystitis and Recurrent Cystitis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1097, doi:10.3390/jcm10051097.

3. Goode, O.; Smith, A.; Zarkan, A.; Cama, J.; Invergo, B.M.; Belgami, D.; Caño-Muñiz, S.; Metz, J.; O’Neill, P.; Jeffries, A.; et al. Persister Escherichia Coli Cells Have a Lower Intracellular PH than Susceptible Cells but Maintain Their PH in Response to Antibiotic Treatment. mBio 2021, 12, 10.1128/mbio.00909-21, doi:10.1128/mbio.00909-21.

4. Robino, L.; Sauto, R.; Morales, C.; Navarro, N.; González, M.J.; Cruz, E.; Neffa, F.; Zeballos, J.; Scavone, P. Presence of Intracellular Bacterial Communities in Uroepithelial Cells, a Potential Reservoir in Symptomatic and Non-Symptomatic People. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 590, doi:10.1186/s12879-024-09489-5.

5. Abell-King, C.; Pokhrel, A.; Rice, S.A.; Duggin, I.G.; Söderström, B. Multispecies Bacterial Invasion of Human Host Cells. Pathog. Dis. 2024, 82, ftae012, doi:10.1093/femspd/ftae012.

6. Zagaglia, C.; Ammendolia, M.G.; Maurizi, L.; Nicoletti, M.; Longhi, C. Urinary Tract Infections Caused by Uropathogenic Escherichia Coli Strains—New Strategies for an Old Pathogen. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1425, doi:10.3390/microorganisms10071425.

7. Yoo, J.-J.; Song, J.S.; Kim, W.B.; Yun, J.; Shin, H.B.; Jang, M.-A.; Ryu, C.B.; Kim, S.S.; Chung, J.C.; Kuk, J.C.; et al. Gardnerella Vaginalis in Recurrent Urinary Tract Infection Is Associated with Dysbiosis of the Bladder Microbiome. 2021, doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-1108904/v1.

8. Morrill, S.; Gilbert, N.M.; Lewis, A.L. Gardnerella Vaginalis as a Cause of Bacterial Vaginosis: Appraisal of the Evidence From in Vivo Models. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 168, doi:10.3389/fcimb.2020.00168.

9. Wang, D.; Haley, E.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.; Zhao, X.; Anderson, L.A.; Allison, J.L.; Stebbins, K.L.; Diaz, M.J.; et al. Emerging and Fastidious Uropathogens Were Detected by M-PCR with Similar Prevalence and Cell Density in Catheter and Midstream Voided Urine Indicating the Importance of These Microbes in Causing UTIs. Infect. Drug Resist. 2023, Volume 16, 7775–7795, doi:10.2147/idr.s429990.

10. Haley, E.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.A.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Anderson, L.A.; Baunoch, D. The Prevalence and Association of Different Uropathogens Detected by M-PCR with Infection-Associated Urine Biomarkers in Urinary Tract Infections. Res. Rep. Urol. 2024, 16, 19–29, doi:10.2147/rru.s443361.

11. Akhlaghpour, M.; Haley, E.; Parnell, L.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.A.; Percaccio, M.; Magallon, J.; Remedios-Chan, M.; Rosas, A.; et al. Urine Biomarkers Individually and as a Consensus Model Show High Sensitivity and Specificity for Detecting UTIs. BMC Infect Dis 2024, 24, 153, doi:10.1186/s12879-024-09044-2.

12. Parnell, L.K.D.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.A.; Haley, E.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Anderson, L.; Baunoch, D. Elevated UTI Biomarkers in Symptomatic Patients with Urine Microbial Densities of 10,000 CFU/ML Indicate a Lower Threshold for Diagnosing UTIs. MDPI 2023, 13, 1–15, doi:10.3390/diagnostics13162688.

13. 2024 WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List (WHO BPPL) Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/376776/9789240093461-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 18 March 2025).

14. Parente, G.; Gargano, T.; Pavia, S.; Cordola, C.; Vastano, M.; Baccelli, F.; Gallotta, G.; Bruni, L.; Corvaglia, A.; Lima, M. Pyelonephritis in Pediatric Uropathic Patients: Differences from Community-Acquired Ones and Therapeutic Protocol Considerations. A 10-Year Single-Center Retrospective Study. Children 2021, 8, 436, doi:10.3390/children8060436.

15. Sachdeva, S.; Rosett, H.A.; Krischak, M.K.; Weaver, K.E.; Heine, R.P.; Denoble, A.E.; Dotters-Katz, S.K. Urinary Tract Infection and Progression to Pyelonephritis: Group B Streptococcus versus E. Coli. Am. J. Perinatol. Rep. 2023, 14, e80–e84, doi:10.1055/s-0044-1779031.

16. Peralta, D.P.; Chang, A.Y. Escherichia Coli: A Rare Cause of Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis. Cureus 2023, 15, e38402, doi:10.7759/cureus.38402.

17. Benaissa, E.; Yasssine, B.L.; Chadli, M.; Maleb, A.; Elouennass, M. Infective Endocarditis Caused by Escherichia Coli of a Native Mitral Valve. IDCases 2021, 24, e01119, doi:10.1016/j.idcr.2021.e01119.

18. Kamat, S.; Sagar, V.V.S.S.; Akhil, C.V.S.; Acharya, S.; Shukla, S.; Kumar, S. Escherichia Coli Urosepsis Leading to Native Valve Endocarditis. J. Pr. Cardiovasc. Sci. 2022, 8, 42–44, doi:10.4103/jpcs.jpcs_7_22.

19. Karunathilake, P.; Kularatne, W.; Bowaththage, S.; Kobbegala, K.; Fasrina, M.; Nasim, F.N.; Costa, M.; Jezeema, Z.; Rajapaksha, R.; Ranawaka, R. Infective Endocarditis with Escherichia Coli Secondary to Urosepsis. 2022, doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-1879210/v1.

20. Wu, Y.; Li, P.; Huang, Z.; Liu, J.; Yang, B.; Zhou, W.; Duan, F.; Wang, G.; Li, J. Four-Year Variation in Pathogen Distribution and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Urosepsis: A Single-Center Retrospective Analysis. Ther. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2024, 11, 20499361241248056, doi:10.1177/20499361241248058.

21. Shahab, K.; Mufti, A.Z.; Iqbal, M.A.; Roghani, M.; Zeb, F.; Amin, U. Assessment of Microbial Diversity Pattern of Sensitivity and Antimicrobial Susceptibility in Patients Admitted with Urosepsis. Ann. PIMS-Shaheed Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto Méd. Univ. 2023, 19, 339–345, doi:10.48036/apims.v19i3.924.

Dr. Emery Haley is a scientific writing specialist with over ten years of experience in translational cell and molecular biology. As both a former laboratory scientist and an experienced science communicator, Dr. Haley is passionate about making complex research clear, approachable, and relevant. Their work has been published in over 10 papers and focuses on bridging the gap between the lab and real-world patient care to help drive better health outcomes.