G. vaginalis

Emery Haley, PhD, Scientific Writing Specialist

Gardnerella vaginalis

Clinical Summary

- G. vaginalis is a nitrite-negative, biofilm-forming, gram-variable microorganism.

- G. vaginalis is fastidious and cannot grow in standard urine culture conditions.

- G. vaginalis is associated with complicated and recurrent UTIs in both males and females.

- In symptomatic UTI patients, G. vaginalis:

- Is not a contaminant (is found in catheter-collected urine specimens).

- Is viable (can grow out in expanded culture conditions).

- Is pathogenic (associated with elevated urine biomarkers of infection).

Bacterial Characteristics

Gram-stain

Gram-variable

Although G. vaginalis lacks an outer membrane, consistent with gram-positive microorganisms, it also has an unusually thin peptidoglycan-containing cell wall. That causes this organism to appear gram-negative, depending on the staining method.

Morphology

Coccobacillus (intermediate between round and rod-shaped)

Growth Requirements

Fastidious

Obligate anaerobe/microaerophile

Nitrate Reduction

No

Urease

Negative

Biofilm Formation

Yes

Pathogenicity

Colonizer or Pathobiont

Clinical Relevance in UTI

Clinically, G. vaginalis is best recognized for its role in bacterial vaginosis (BV).[1] This fastidious organism is typically considered a colonizer of the vaginal microbiome and has previously been dismissed as a contaminant when detected in midstream voided urine specimens.[2,3] However, studies of the vaginal and bladder microbiomes have found that these two microbiomes have a high similarity within one individual, suggesting important interconnectivity of these microbial communities.[4–6]

Despite associations with the vaginal microbiome and BV, the clinical relevance of G. vaginalis is not limited to adult females. G. vaginalis has been detected in voided urine specimens of both pediatric female patients [7,8] and adult patients (both male and female) [9] with clinically suspected UTI. G. vaginalis has been recovered from the urinary tract of men, potentially via exposure from female sexual partners.[10–12] Though uncommon, G. vaginalis prostatitis [13] and bacteremia secondary to urinary tract infection (UTI) [14] have also been reported in men.

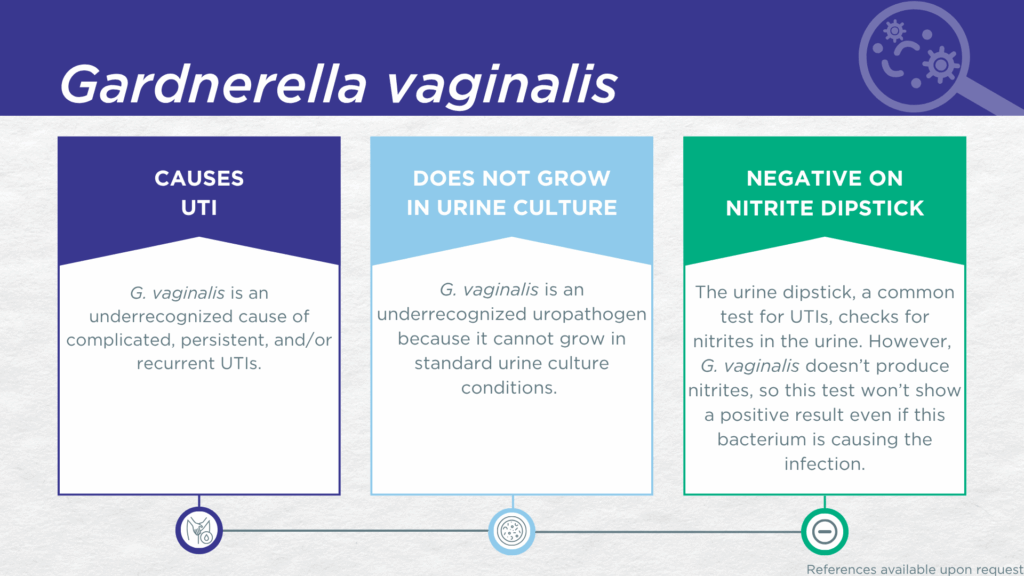

G. vaginalis UTI is underdiagnosed because the organism lacks nitrate reductase activity, so screening strategies involving urinalysis for nitrite positivity will be false-negative.[15,16] Additionally, growing G. vaginalis in culture requires an anaerobic atmosphere which is not typically used in clinical laboratories performing standard culture techniques for UTI diagnosis.[17] Instead, G. vaginalis UTI is most often diagnosed by advanced molecular techniques, including polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and sequencing.[8,18,19]

G. vaginalis has recently been specifically linked to both urobiome dysbiosis and recurrent UTIs (rUTIs) [1,18] and pre-clinical studies have demonstrated that transurethral exposure of bladder cells to G. vaginalis triggers immune activation, urothelial exfoliation, and rUTI due to the emergence of uropathogenic E. coli from bladder reservoirs. A study using expanded quantitative urine culture (EQUC), a technique growing a larger urine volume with additional nutritional media, different atmospheric conditions, and longer incubations, found that the organism was viable.[20] In a study of older adult males and females with clinically suspected complicated UTI, G. vaginalis was detected in both midstream voided and in-and-out-catheter collected specimens, indicating that it was truly present in the bladder, not simply a contaminant picked up during voiding.[19] Furthermore, elevated markers of immune system activation in the urinary tract have been measured from the same clinical urine specimens in which G. vaginalis was detected, indicating that the presence of G. vaginalis was associated with an immune response to urinary tract infection.[21–23]

Together, these findings demonstrate the value of detecting this organism and indicate that G. vaginalis should be seriously considered as a uropathogen when detected in any individual with UTI symptoms.

Treatment

Evidence of Efficacy (Checkmarks) [14,24–26]: Ampicillin

For G. vaginalis UTI, oral ampicillin and oral metronidazole are the recommended treatment options.[26] Standard treatment regimens for vaginal G. vaginalis in BV involve oral metronidazole, intravaginal topical metronidazole gel, or intravaginal topical clindamycin cream.[25] Studies and case reports have also indicated amoxicillin/clavulanate, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, ciprofloxacin, and vancomycin as clinically effective against systemic G. vaginalis infection.[14,24]

1. Morrill, S.; Gilbert, N.M.; Lewis, A.L. Gardnerella Vaginalis as a Cause of Bacterial Vaginosis: Appraisal of the Evidence From in Vivo Models. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 168, doi:10.3389/fcimb.2020.00168.

2. Jespers, V.; Hardy, L.; Buyze, J.; Loos, J.; Buvé, A.; Crucitti, T. Association of Sexual Debut in Adolescents With Microbiota and Inflammatory Markers. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 128, 22–31, doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000001468.

3. Hickey, R.J.; Zhou, X.; Settles, M.L.; Erb, J.; Malone, K.; Hansmann, M.A.; Shew, M.L.; Pol, B.V.D.; Fortenberry, J.D.; Forney, L.J. Vaginal Microbiota of Adolescent Girls Prior to the Onset of Menarche Resemble Those of Reproductive-Age Women. mBio 2015, 6, e00097-15, doi:10.1128/mbio.00097-15.

4. Thomas-White, K.; Forster, S.C.; Kumar, N.; Kuiken, M.V.; Putonti, C.; Stares, M.D.; Hilt, E.E.; Price, T.K.; Wolfe, A.J.; Lawley, T.D. Culturing of Female Bladder Bacteria Reveals an Interconnected Urogenital Microbiota. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 1557, doi:10.1038/s41467-018-03968-5.

5. Komesu, Y.M.; Dinwiddie, D.L.; Richter, H.E.; Lukacz, E.S.; Sung, V.W.; Siddiqui, N.Y.; Zyczynski, H.M.; Ridgeway, B.; Rogers, R.G.; Arya, L.A.; et al. Defining the Relationship between Vaginal and Urinary Microbiomes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 222, 154.e1-154.e10, doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.08.011.

6. Putonti, C.; Thomas-White, K.; Crum, E.; Hilt, E.E.; Price, T.K.; Wolfe, A.J. Genome Investigation of Urinary Gardnerella Strains and Their Relationship to Isolates of the Vaginal Microbiota. mSphere 2021, 6, 10.1128/msphere.00154-21, doi:10.1128/msphere.00154-21.

7. Shioji, Y.; Yaginuma, M.; Ota, M.; Inoguchi, T.; Furuichi, M.; Shinjoh, M.; Takahashi, T. Gram Staining to Detect Gardnerella Vaginalis Urinary Tract Infection in a Child. Pediatr. Int. 2023, 65, e15607, doi:10.1111/ped.15607.

8. Bhavsar, S.M.; Polavarapu, N.; Haley, E.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Chen, X.; Havrilla, J.; Baunoch, D.; Lieberman, K. Noninferiority of Multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction Compared to Standard Urine Culture for Urinary Tract Infection Diagnosis in Pediatric Patients at Hackensack Meridian Health Children’s Hospital Emergency Department. Pediatr. Heal., Med. Ther. 2024, 15, 351–364, doi:10.2147/phmt.s491929.

9. Haley, E.; Luke, N.; Korman, H.; Baunoch, D.; Wang, D.; Zhao, X.; Mathur, M. Improving Patient Outcomes While Reducing Empirical Treatment with Multiplex-Polymerase-Chain-Reaction/Pooled-Antibiotic-Susceptibility-Testing Assay for Complicated and Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023, 13, doi:10.3390/diagnostics13193060.

10. Dawson, S.G.; Ison, C.A.; Csonka, G.; Easmon, C.S.F. Male Carriage of Gardnerella Vaginalis. Br. J. Vener. Dis. 1982, 58, 243, doi:10.1136/sti.58.4.243.

11. Holst, E.; Mårdh, P.A.; Thelin, I. Recovery of Anaerobic Curved Rods and Gardnerella Vaginalis from the Urethra of Men, Including Male Heterosexual Consorts of Female Carriers. Scand. J. Urol. Nephrol. Suppl. 1984, 86, 173–177.

12. Boyanova, L.; Marteva-Proevska, Y.; Gergova, R.; Markovska, R. Gardnerella Vaginalis in Urinary Tract Infections, Are Men Spared? Anaerobe 2021, 72, 102438, doi:10.1016/j.anaerobe.2021.102438.

13. McCormick, M.E.; Herbert, M.T.; Pewitt, E.B. Gardnerella Vaginalis Prostatitis and Its Treatment: A Case Report. Urol. Case Rep. 2022, 40, 101874, doi:10.1016/j.eucr.2021.101874.

14. Akamine, C.M.; Chou, A.; Tavakoli-Tabasi, S.; Musher, D.M. Gardnerella Vaginalis Bacteremia in Male Patients: A Case Series and Review of the Literature. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, ofac176, doi:10.1093/ofid/ofac176.

15. BacDive | The Bacterial Diversity Metadatabase Available online: https://bacdive.dsmz.de/ (accessed on 11 February 2025).

16. BioCyc Pathway/Genome Database Collection Available online: https://biocyc.org/ (accessed on 11 February 2025).

17. Legaria, M.C.; Barberis, C.; Famiglietti, A.; Gregorio, S.D.; Stecher, D.; Rodriguez, C.H.; Vay, C.A. Urinary Tract Infections Caused by Anaerobic Bacteria. Utility of Anaerobic Urine Culture. Anaerobe 2022, 78, 102636, doi:10.1016/j.anaerobe.2022.102636.

18. Yoo, J.-J.; Song, J.S.; Kim, W.B.; Yun, J.; Shin, H.B.; Jang, M.-A.; Ryu, C.B.; Kim, S.S.; Chung, J.C.; Kuk, J.C.; et al. Gardnerella Vaginalis in Recurrent Urinary Tract Infection Is Associated with Dysbiosis of the Bladder Microbiome. 2021, doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-1108904/v1.

19. Wang, D.; Haley, E.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.; Zhao, X.; Anderson, L.A.; Allison, J.L.; Stebbins, K.L.; Diaz, M.J.; et al. Emerging and Fastidious Uropathogens Were Detected by M-PCR with Similar Prevalence and Cell Density in Catheter and Midstream Voided Urine Indicating the Importance of These Microbes in Causing UTIs. Infect. Drug Resist. 2023, Volume 16, 7775–7795, doi:10.2147/idr.s429990.

20. Festa, R.A.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Parnell, L.; Wang, D.; Zhao, X.; Magallon, J.; Remedios-Chan, M.; Nguyen, J.; Cho, T.; et al. A Test Combining Multiplex-PCR with Pooled Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing Has High Correlation with Expanded Urine Culture for Detection of Live Bacteria in Urine Samples of Suspected UTI Patients. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2023, 107, 116015, doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2023.116015.

21. Haley, E.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.A.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Anderson, L.A.; Baunoch, D. The Prevalence and Association of Different Uropathogens Detected by M-PCR with Infection-Associated Urine Biomarkers in Urinary Tract Infections. Res. Rep. Urol. 2024, 16, 19–29, doi:10.2147/rru.s443361.

22. Akhlaghpour, M.; Haley, E.; Parnell, L.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.A.; Percaccio, M.; Magallon, J.; Remedios-Chan, M.; Rosas, A.; et al. Urine Biomarkers Individually and as a Consensus Model Show High Sensitivity and Specificity for Detecting UTIs. BMC Infect Dis 2024, 24, 153, doi:10.1186/s12879-024-09044-2.

23. Parnell, L.K.D.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.A.; Haley, E.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Anderson, L.; Baunoch, D. Elevated UTI Biomarkers in Symptomatic Patients with Urine Microbial Densities of 10,000 CFU/ML Indicate a Lower Threshold for Diagnosing UTIs. MDPI 2023, 13, 1–15, doi:10.3390/diagnostics13162688.

24. Ruiz-Gómez, M.L.; Martín-Way, D.A.; Pérez-Ramírez, M.D.; Gutiérrez-Fernández, J. [Male deep infections by Gardnerella vaginalis. A literature review and a case report]. Rev Esp Quimioter 2019, 32, 469–472.

25. Li, T.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, F.; He, Y.; Zong, X.; Bai, H.; Liu, Z. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Metronidazole and Clindamycin against Gardnerella Vaginalis in Planktonic and Biofilm Formation. 2020, 1361825.

26. Pedraza-Avilés, A.G.; Zaragoza, M.C.; Mota-Vázquez, R.; Hernández-Soto, C.; Ramírez-Santana, M.; Terrazas-Maldonado, M.L. Treatment of Urinary Tract Infection by Gardnerella Vaginalis: A Comparison of Oral Metronidazole versus Ampicillin. Revista Latinoamericana De Microbiol 2001, 43, 65–69.

Dr. Emery Haley is a scientific writing specialist with over ten years of experience in translational cell and molecular biology. As both a former laboratory scientist and an experienced science communicator, Dr. Haley is passionate about making complex research clear, approachable, and relevant. Their work has been published in over 10 papers and focuses on bridging the gap between the lab and real-world patient care to help drive better health outcomes.