Viridans Group Streptococci

Emery Haley, PhD, Scientific Writing Specialist

Clinical Summary

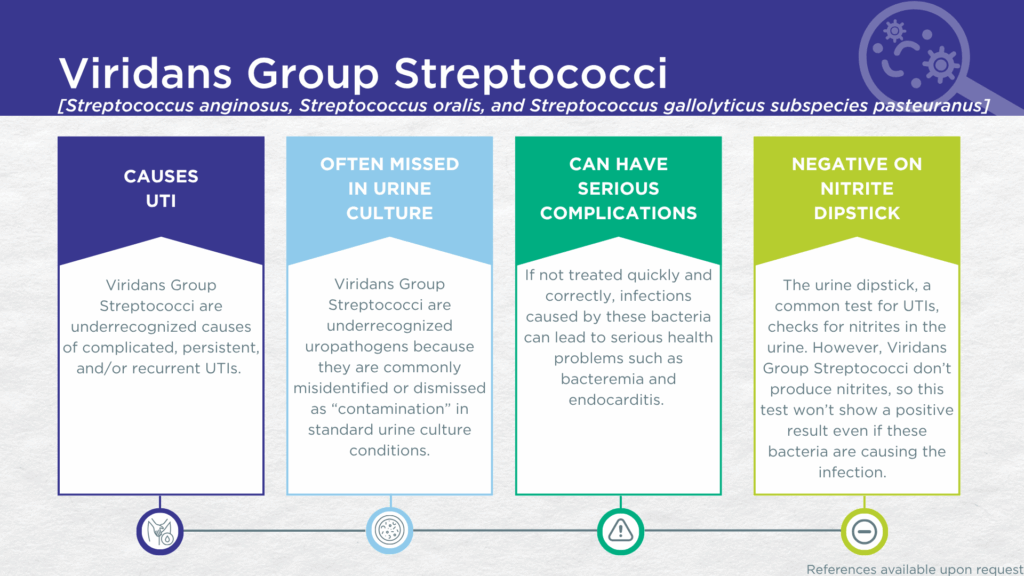

- Viridans Group Streptococci (VGS) are nitrite-negative, biofilm-forming, gram-positive microorganisms.

- VGS are commonly dismissed as contaminants in standard urine culture conditions.

- VGS are associated with complicated, persistent, and/or recurrent UTIs.

- In symptomatic UTI patients, VGS:

- Are not contaminants (are found in catheter-collected urine specimens).

- Are viable (can grow out on culture).

- Are pathogenic (associated with elevated urine biomarkers of infection).

- Reported severe complications of VGS UTI include bacteremia and endocarditis.

Bacterial Characteristics

Gram-stain

Gram-positive (all)

Morphology

Coccus (all)

Growth Requirements

Non-fastidious (all grow well in standard urine culture conditions)

- S. anginosus is a microaerophile

- S. oralis and S. pasteuranus are facultative anaerobes

*Note: We do not perform P-AST™ on Streptococci (including Viridans Group Streptococci). Streptococci have well-established and predictably high susceptibilities to beta-lactam antibiotics, particularly penicillin and ampicillin (see treatment section). Therefore, confirmation of susceptibility by P-AST™ assay is unnecessary.

Nitrate Reduction

No (except S. oralis is variable for this phenotype)

Urease

Negative (all)

Biofilm Formation

Yes (all)

Pathogenicity

Colonizer or Pathobiont

Clinical Relevance in UTI

Viridans Group Streptococci (VGS) is a historic pseudo-taxonomic term for several Streptococcus species traditionally described as gram-positive commensals of the human microbiome.[1] In the Guidance® UTI assay, this group term specifically encompasses three species, S. anginosus, S. oralis, and S. pasteuranus.

S. anginosus

The best-studied of these species, S. anginosus, was first described in 1906.[2] Genetic sequencing studies have confirmed that virtually identical strains of S. anginosus are present in both the vagina and bladder of same subject,[3,4] consistent with the reported interactions between vaginal and urinary microbiomes.[3,5] S. anginosus, has been identified by expanded quantitative urine culture (EQUC) in catheter-obtained urine specimens from women with various lower urinary tract disorders, including interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS),[6] and UTI,[8–10] at higher densities and with higher frequency than among asymptomatic women. These findings suggest that S. anginosus is involved in dysbiosis of urogenital microbiomes and may act as an opportunistic uropathogen.[11] Indeed S. anginosus is known to act as an opportunistic uropathogen at other body sites in immune compromised individuals.[12] S. anginosus has also been associated with recurrent UTI,[13,14] and with severe complications including bacteremia[15] and endocarditis[16,17].

S. oralis

Though less well studied, S. oralis (part of the S. mitis subgroup of VGS) has also been associated with urogenital microbiome dysbiosis[18] and complicated UTI, particularly in immune compromised individuals[19–22] . S. oralis UTI may lead to severe complications including bacteremia,[22,23] peritonitis,[22,24] endocarditis,[22,25] and meningitis[22,26] .

S. pasteuranus

Though less well studied, S. pasteuranus (part of the S. bovis subgroup of VGS) has also been associated with complicated, persistent, and recurrent UTI, particularly in neonates, older adults, pregnant women, and immune compromised individuals.[27–31] S. pasteuranus UTI may lead to severe complications including bacteremia,[29,31] endocarditis,[30] meningitis,[32] and sepsis[32].

The Viridans Streptococci Group

VGS UTIs are likely significantly underdiagnosed for a couple of reasons. Firstly, VGS organisms generally lack nitrate reductase activity, so screening strategies involving urinalysis for nitrite positivity will be false-negative.[33,34] Secondly, although the organisms grow readily in standard urine culture conditions, they are commonly dismissed as irrelevant gram-positive commensal organisms of the urogenital microbiome and labeled as a “contaminant”. [1]

However, in a study of older adult males and females with clinically suspected complicated UTI, VGS was detected in both midstream voided and in-and-out-catheter collected specimens indicating that it was truly present in the bladder, not simply a contaminant picked up during voiding.[35] Furthermore, elevated markers of immune system activation in the urinary tract have been measured from the same clinical urine specimens in which VGS was detected, indicating that the presence of VGS was associated with an immune response to urinary tract infection.[36–38]

Despite their reputation as contaminants, VGS (S. anginosus, S. oralis, and S. pasteuranus) are all associated with complicated, persistent, and/or recurrent UTIs, as well as with severe complications such as bacteremia and endocarditis. Together, these findings indicate that VGS should be seriously considered as a uropathogen and demonstrate the value of detecting these organisms, particularly in individuals with immune compromise or other risk factors for complicated, persistent, or recurrent UTI.

Treatment

Evidence of Efficacy (Checkmarks): Ampicillin, Cefepime, Ceftriaxone, Levofloxacin, Linezolid, Meropenem, and Vancomycin.

Because Streptococci have well-established and predictably high susceptibilities to beta-lactam antibiotics, confirmation of susceptibility by P-AST™ assay is unnecessary. To provide faster result reporting without compromising relevant treatment options, Pathnostics provides a report without P-AST™ for monomicrobial Streptococci. See the checkmarks for suggested treatment options.

1. Archer, G.T.L. Streptococcus Viridans in Urine. J. R. Army Méd. Corps 1938, 70, 97, doi:10.1136/jramc-70-02-03.

2. Andrewes, F.W.; Horder, T.J. A STUDY OF THE STREPTOCOCCI PATHOGENIC FOR MAN. Lancet 1906, 168, 852–855, doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(01)43302-2.

3. Thomas-White, K.; Forster, S.C.; Kumar, N.; Kuiken, M.V.; Putonti, C.; Stares, M.D.; Hilt, E.E.; Price, T.K.; Wolfe, A.J.; Lawley, T.D. Culturing of Female Bladder Bacteria Reveals an Interconnected Urogenital Microbiota. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 1557, doi:10.1038/s41467-018-03968-5.

4. Chen, Y.B.; Hochstedler, B.; Pham, T.T.; Acevedo-Alvarez, M.; Mueller, E.R.; Wolfe, A.J. The Urethral Microbiota: A Missing Link in the Female Urinary Microbiota. J Urol 2020, 204, 303–309, doi:10.1097/ju.0000000000000910.

5. Komesu, Y.M.; Dinwiddie, D.L.; Richter, H.E.; Lukacz, E.S.; Sung, V.W.; Siddiqui, N.Y.; Zyczynski, H.M.; Ridgeway, B.; Rogers, R.G.; Arya, L.A.; et al. Defining the Relationship between Vaginal and Urinary Microbiomes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 222, 154.e1-154.e10, doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.08.011.

6. Jacobs, K.M.; Price, T.K.; Thomas-White, K.; Halverson, T.; Davies, A.; Myers, D.L.; Wolfe, A.J. Cultivable Bacteria in Urine of Women With Interstitial Cystitis: (Not) What We Expected. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 2021, 27, 322–327, doi:10.1097/spv.0000000000000854.

7. Pearce, M.M.; Zilliox, M.J.; Rosenfeld, A.B.; Thomas-White, K.J.; Richter, H.E.; Nager, C.W.; Visco, A.G.; Nygaard, I.E.; Barber, M.D.; Schaffer, J.; et al. The Female Urinary Microbiome in Urgency Urinary Incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015, 213, 347.e1-347.e11, doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.07.009.

8. Price, T.K.; Hilt, E.E.; Dune, T.J.; Mueller, E.R.; Wolfe, A.J.; Brubaker, L. Urine Trouble: Should We Think Differently about UTI? Int Urogynecol J 2018, 29, 205–210, doi:10.1007/s00192-017-3528-8.

9. Price, T.K.; Dune, T.; Hilt, E.E.; Thomas-White, K.J.; Kliethermes, S.; Brincat, C.; Brubaker, L.; Wolfe, A.J.; Mueller, E.R.; Schreckenberger, P.C. The Clinical Urine Culture: Enhanced Techniques Improve Detection of Clinically Relevant Microorganisms. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2016, 54, 1216–1222, doi:10.1128/jcm.00044-16.

10. Hochstedler-Kramer, B.; Joyce, C.; Abdul-Rahim, O.; Barnes, H.C.; Mueller, E.R.; Wolfe, A.J.; Brubaker, L.; Burnett, L.A. One Size Does Not Fit All: Variability in Urinary Symptoms and Microbial Communities. Front. Urol. 2022, 2, 890990, doi:10.3389/fruro.2022.890990.

11. Moreland, R.B.; Choi, B.I.; Geaman, W.; Gonzalez, C.; Hochstedler-Kramer, B.R.; John, J.; Kaindl, J.; Kesav, N.; Lamichhane, J.; Lucio, L.; et al. Beyond the Usual Suspects: Emerging Uropathogens in the Microbiome Age. Frontiers in Urology 2023, 3, doi:10.3389/fruro.2023.1212590.

12. Guerrero-Del-Cueto, F.; Ibanes-Gutiérrez, C.; Velázquez-Acosta, C.; Cornejo-Juárez, P.; Vilar-Compte, D. Microbiology and Clinical Characteristics of Viridans Group Streptococci in Patients with Cancer. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 22, 323–327, doi:10.1016/j.bjid.2018.06.003.

13. Prasad, A.; Ene, A.; Jablonska, S.; Du, J.; Wolfe, A.J.; Putonti, C. Comparative Genomic Study of Streptococcus Anginosus Reveals Distinct Group of Urinary Strains. mSphere 2023, 8, e00687-22, doi:10.1128/msphere.00687-22.

14. Miller, S.; Miller-Ensminger, T.; Voukadinova, A.; Wolfe, A.J.; Putonti, C. Draft Genome Sequence of Streptococcus Anginosus UMB7768, Isolated from a Woman with Recurrent UTI Symptoms. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2020, 9, e00418-20, doi:10.1128/mra.00418-20.

15. Wu, H.; Zheng, R. Splenic Abscess Caused by Streptococcus Anginosus Bacteremia Secondary to Urinary Tract Infection: A Case Report and Literature Review. Open Med. 2020, 15, 997–1002, doi:10.1515/med-2020-0117.

16. Chang, K.-M.; Hsieh, S.L.; Koshy, R. An Unusual Case of Streptococcus Anginosus Endocarditis in a Healthy Host With Bicuspid Aortic Valve. Cureus 2021, 13, e13171, doi:10.7759/cureus.13171.

17. Finn, T.; Schattner, A.; Dubin, I.; Cohen, R. Streptococcus Anginosus Endocarditis and Multiple Liver Abscesses in a Splenectomised Patient. BMJ Case Rep. 2018, 2018, bcr-2018-224266, doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-224266.

18. Mores, C.R.; Price, T.K.; Wolff, B.; Halverson, T.; Limeira, R.; Brubaker, L.; Mueller, E.R.; Putonti, C.; Wolfe, A.J. Genomic Relatedness and Clinical Significance of Streptococcus Mitis Strains Isolated from the Urogenital Tract of Sexual Partners. Microb Genom 2021, 7, mgen000535, doi:10.1099/mgen.0.000535.

19. Chou, Y.-S.; Horng, C.-T.; Huang, H.-S.; Hu, S.-C.; Chen, J.-T.; Tsai, M.-L. Reactive Arthritis Following Streptococcus Viridans Urinary Tract Infection. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2010, 18, 52–53, doi:10.3109/09273940903414517.

20. Ong, G.; Barr, J.G.; Savage, M. Streptococcus Mitis: Urinary Tract Infection in a Renal Transplant Patient. J. Infect. 1998, 37, 91–92, doi:10.1016/s0163-4453(98)91421-9.

21. Zhang, B.; Zhou, J.; Xie, G.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, K.; Feng, T.; Yang, S. A Case of Urinary Tract Infection Caused by Multidrug Resistant Streptococcus Mitis/Oralis. Infect. Drug Resist. 2023, 16, 4285–4288, doi:10.2147/idr.s416387.

22. Ren, J.; Sun, P.; Wang, M.; Zhou, W.; Liu, Z. Insights into the Role of Streptococcus Oralis as an Opportunistic Pathogen in Infectious Diseases. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1480961, doi:10.3389/fcimb.2024.1480961.

23. Basaranoglu, S.T.; Ozsurekci, Y.; Aykac, K.; Aycan, A.E.; Bıcakcigil, A.; Altun, B.; Sancak, B.; Cengiz, A.B.; Kara, A.; Ceyhan, M. Streptococcus Mitis/Oralis Causing Blood Stream Infections in Pediatric Patients. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 72, 1–6, doi:10.7883/yoken.jjid.2018.074.

24. Kotani, A.; Oda, Y.; Hirakawa, Y.; Nakamura, M.; Hamasaki, Y.; Nangaku, M. Peritoneal Dialysis-Related Peritonitis Caused by Streptococcus Oralis. Intern. Med. 2021, 60, 3447–3452, doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.6234-20.

25. Seo, H.; Hyun, J.; Kim, H.; Park, S.; Chung, H.; Bae, S.; Jung, J.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, S.-H.; Lee, S.-O.; et al. Risk and Outcome of Infective Endocarditis in Streptococcal Bloodstream Infections According to Streptococcal Species. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e01049-23, doi:10.1128/spectrum.01049-23.

26. Cardoso, J.; Ferreira, D.; Assis, R.; Monteiro, J.; Coelho, I.; Real, A.; Catorze, N. Streptococcus Oralis Meningitis. Eur. J. Case Rep. Intern. Med. 2021, 8, 002349, doi:10.12890/2021_002349.

27. Poulsen, L.; Bisgaard, M.; Son, N.; Trung, N.; An, H.; Dalsgaard, A. Enterococcus and Streptococcusspp. Associated with Chronic and Self-Medicated Urinary Tract Infections in Vietnam. BMC Infectious Diseases 2012, 12, 320, doi:10.1186/1471-2334-12-320.

28. Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Zeng, J.; Yang, J.; Lu, B. Microbiological and Clinical Characteristics of Streptococcus Gallolyticus Subsp. Pasteurianus Infection in China. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 791, doi:10.1186/s12879-019-4413-5.

29. Teresa-Alguacil, J. de; Gutiérrez-Soto, M.; Rodríguez-Granger, J.; Osuna-Ortega, A.; Navarro-Marí, J.M.; Gutiérrez-Fernández, J. Clinical Interest of Streptococcus Bovis Isolates in Urine. Rev. espanola Quimioter. : publicacion Of. Soc. Espanola Quimioter. 2016, 29, 155–158.

30. Pereira, C.; Nogueira, F.; Marques, J.C.; Ferreira, J.P.; Almeida, J.S. Endocarditis by Streptococcus Pasteurianus. Cureus 2023, 15, e34529, doi:10.7759/cureus.34529.

31. Matesanz, M.; Rubal, D.; Iñiguez, I.; Rabuñal, R.; García-Garrote, F.; Coira, A.; García-País, M.J.; Pita, J.; Rodriguez-Macias, A.; López-Álvarez, M.J.; et al. Is Streptococcus Bovis a Urinary Pathogen? Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2015, 34, 719–725, doi:10.1007/s10096-014-2273-x.

32. Zou, D.; Li, F.; Jiao, S.-L.; Dong, J.-R.; Xiao, Y.-Y.; Yan, X.-L.; Li, Y.; Ren, D. Infantile Bacterial Meningitis Combined with Sepsis Caused by Streptococcus Gallolyticus Subspecies Pasteurianus: A Case Report. World J. Clin. Cases 2024, 12, 6472–6478, doi:10.12998/wjcc.v12.i31.6472.

33. BacDive | The Bacterial Diversity Metadatabase Available online: https://bacdive.dsmz.de/ (accessed on 11 February 2025).

34. BioCyc Pathway/Genome Database Collection Available online: https://biocyc.org/ (accessed on 11 February 2025).

35. Wang, D.; Haley, E.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.; Zhao, X.; Anderson, L.A.; Allison, J.L.; Stebbins, K.L.; Diaz, M.J.; et al. Emerging and Fastidious Uropathogens Were Detected by M-PCR with Similar Prevalence and Cell Density in Catheter and Midstream Voided Urine Indicating the Importance of These Microbes in Causing UTIs. Infect. Drug Resist. 2023, Volume 16, 7775–7795, doi:10.2147/idr.s429990.

36. Haley, E.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.A.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Anderson, L.A.; Baunoch, D. The Prevalence and Association of Different Uropathogens Detected by M-PCR with Infection-Associated Urine Biomarkers in Urinary Tract Infections. Res. Rep. Urol. 2024, 16, 19–29, doi:10.2147/rru.s443361.

37. Akhlaghpour, M.; Haley, E.; Parnell, L.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.A.; Percaccio, M.; Magallon, J.; Remedios-Chan, M.; Rosas, A.; et al. Urine Biomarkers Individually and as a Consensus Model Show High Sensitivity and Specificity for Detecting UTIs. BMC Infect Dis 2024, 24, 153, doi:10.1186/s12879-024-09044-2.

38. Parnell, L.K.D.; Luke, N.; Mathur, M.; Festa, R.A.; Haley, E.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Anderson, L.; Baunoch, D. Elevated UTI Biomarkers in Symptomatic Patients with Urine Microbial Densities of 10,000 CFU/ML Indicate a Lower Threshold for Diagnosing UTIs. MDPI 2023, 13, 1–15, doi:10.3390/diagnostics13162688.

Dr. Emery Haley is a scientific writing specialist with over ten years of experience in translational cell and molecular biology. As both a former laboratory scientist and an experienced science communicator, Dr. Haley is passionate about making complex research clear, approachable, and relevant. Their work has been published in over 10 papers and focuses on bridging the gap between the lab and real-world patient care to help drive better health outcomes.